Cyber Security News Aggregator

.Cyber Tzar

provide acyber security risk management

platform; including automated penetration tests and risk assesments culminating in a "cyber risk score" out of 1,000, just like a credit score.When is a Scrape a Breach?

published on 2021-12-16 07:32:07 UTC by Troy HuntContent:

A decade and a bit ago during my tenure at Pfizer, a colleague's laptop containing information about customers, healthcare providers and other vendors was stolen from their car. The machine had full disk encryption and it's not known whether the thief was ever actually able to access the data. It's not clear if the car was locked or not. Is this a data breach?

Some years later, an outsourcing provider of the Australian Red Cross Blood Service copied a database from production and backed it up to a web server facing the world. Someone stumbled across it, downloaded it and then sent it to me. It was the largest incident of it's kind in Australia and it included my own personal data. No security controls were breached by the person who downloaded it, they simply accessed a publicly available file. Same question again - breach or not?

The whole discussion around what constitutes a breach came up again last week after I loaded email addresses scraped off Gravatar into Have I Been Pwned (HIBP). This incident was originally in the news back in October last year when a security researcher found this one neat trick to access a Gravatar profile:

http://en.gravatar.com/1428.jsonHad you changed that number in the URL to 7888985, you would have seen this record:

{

"entry" : [

{

"id" : "7888985",

"hash" : "4f2269dfd9414dc2b982f828e9574b57",

"requestHash" : "troyhunt",

"profileUrl" : "http : //gravatar.com/troyhunt",

"preferredUsername" : "troyhunt",

"thumbnailUrl" : "http : //1.gravatar.com/avatar/4f2269dfd9414dc2b982f828e9574b57",

"photos" : [

{

"value" : "http : //1.gravatar.com/avatar/4f2269dfd9414dc2b982f828e9574b57",

"type" : "thumbnail"

}

],

"name" : {

"givenName" : "Troy",

"familyName" : "Hunt",

"formatted" : "Troy Hunt"

},

"displayName" : "troyhunt",

"currentLocation" : "Australia",

"urls" : [

]

}

]

}Yep, oldest trick in the book, "insecure direct object references" where you simply change a part of the URL to a predictable value and get back a different record. So, someone did that 167 million times, dumped the data and shared it on a popular hacking forum. But this is public profile information - stuff I consciously added to Gravatar knowing it would be publicly accessible - so is it a breach? Let's explore that idea further.

Defining "Breach"

So, which - if any - of the 3 examples above constitutes a breach? The first one resulted in Pfizer reporting the incident to the state's Attorney General so clearly they treated it as such. As for the second one, 3 days after I reported it to them the CEO did a press conference where she reported the incident so obviously, they also treated it as a breach. Gravatar? Not hacked:

Gravatar was not hacked. Our service gives you control over the data you want to share online. The data you choose to share publicly is made available via our API. Users can choose to share their full name, display name, location, email address, and a short biography.

— Gravatar.com (@gravatar) December 6, 2021

(2/4)

But... the Red Cross wasn't hacked either and that was clearly a data breach. The problem I have with this statement is that it conflates the activity that granted access to the data with the privacy impact of the data falling into the wrong hands. The FAQ they published after I loaded the data into HIBP uses the same "hack" term:

While this incident was a misuse of our service, it was not a hack. No security protocols were breached.

I mostly agree with this, at least the second sentence (the first sentence deserves a blog post of it's own about "When is a Hack a Hack?") This incident didn't involve breaching a security protocol, at least not in your classic SQL injection style where a coding flaw allowed someone to literally hack the system and breach the data. But again, the means of access can't be the determining factor as to whether or not a breach has occurred.

A data breach is a security violation, in which sensitive, protected or confidential data is copied, transmitted, viewed, stolen or used by an individual unauthorized to do so.

But that wouldn't fit the Red Cross scenario. It also doesn't work for the 24 million Lumin PDF accounts that were taken from a MongoDB instance "left exposed online without a password" as no security was violated. It doesn't work for the 59 million Modern Business Solutions records "left exposed online". I could go on, but you get the idea.

Edit (the next day): In response to this post, someone pointed me to Meta including scraping vectors within their bug bounty program. This is really interesting as it elevates the significance of scraping up into the realms of what we'd consider more traditional attacks that would qualify for a bounty (such as SQL injection). It's also interesting given Facebook's scraping incident earlier in the year and their defence of it...

But is it Notifiable?

Gravatar didn't notify impacted parties of this incident. Then again, neither did LinkedIn earlier this year or Facebook before them. All of them stuck with the line that scraping != breach therefore there's nothing to notify anyone about. Facebook actually stated in their writeup on scraping that it was "in violation of our terms of service", which immediately made me think of this zinger:

Posting it to you is secure, as it's illegal to open someone else's mail. ^JGS

— Virgin Media (@virginmedia) August 17, 2019

Ah, that one will never get old!

Let's look at it this way: Facebook published that piece after I loaded the scraped data into HIBP and a whole bunch of people got pissed. Gravatar posted their FAQ well over a year after initial reporting of the incident, but only just after I loaded it into HIBP where many people responded in an equally pissed fashion.

Here's the important truth about scraping: public data or not, most people don't expect it to be used in that fashion and they're upset when it happens. They want answers. It shouldn't be my job as one guy sitting here running a free data breach service in his spare time to tell people their data has been inappropriately accessed, redistributed and in all likelihood, abused.

And while I'm here debunking the relevancy of the notifiability of a breach, check out the criteria for a breach down here in Australia to qualify as "notifiable":

The NDB scheme requires regulated entities to notify particular individuals and the Commissioner about ‘eligible data breaches’. A data breach is eligible if it is likely to result in serious harm to any of the individuals to whom the information relates.

So... let's say catforum.com.au gets dumped and all the plain text passwords spread around the internet alongside email addresses and usernames. But hey, it's just cats, who cares, right? No serious harm? Well if you work to the definition of being guided by "the viewpoint of a reasonable person", no. But if you understand how data breaches, users and hackers all work, there's the keys to a bunch of cat lovers digital lives due to the prevalence of password reuse. This is just the ultimate Aussie "she'll be right mate" approach to respecting personal data.

The point is that just because you don't notify impacted individuals or even don't have to, doesn't mean it's not a breach and that people want to know about it.

Does it Even Matter?

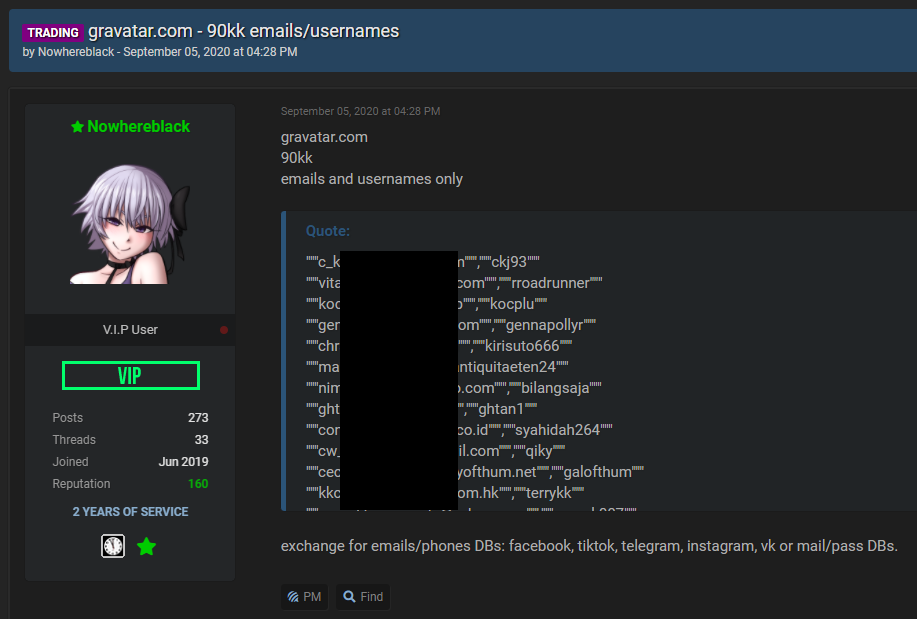

In researching the Gravatar incident before I published the email addresses to HIBP, I found this piece on a popular hacking forum:

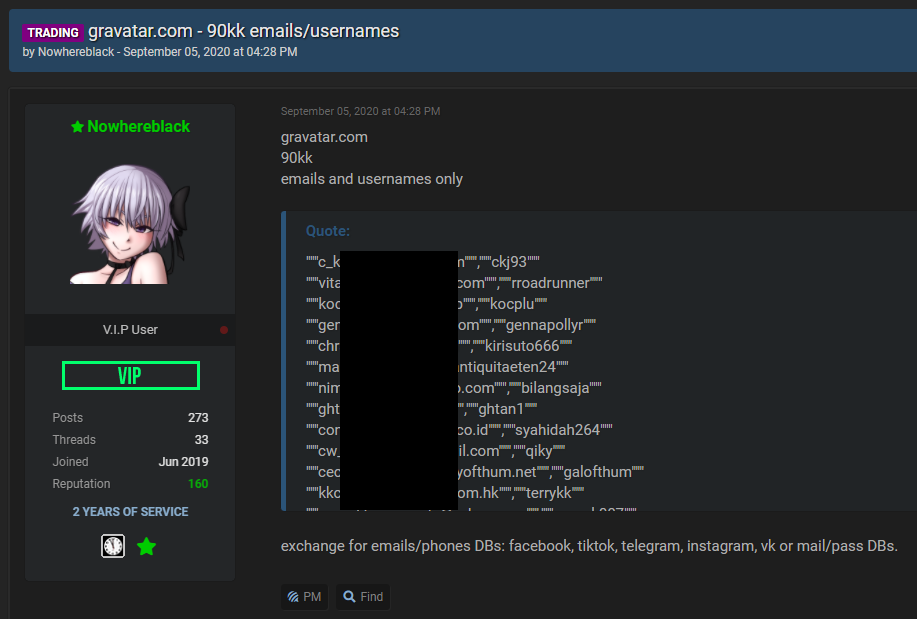

So, to the title of this section, does it matter if you call it a breach or not? People have taken this data and are exchanging with others. Why? Well it's not to send them Christmas cards, I'll tell you that for sure! Another thread appeared on the same forum once the incident got press after going into HIBP, this time with someone selling the data. The first response in the thread is this one:

Uh, maybe they're sending localised Christmas cards?! Or perhaps the username on that account gives you a more accurate sense of what they intend to do with the addresses. That particular thread continues with the buyer seeking out Bulgarian email addresses, to which the seller advises there are over 100k addresses on .bg TLDs.

And per the previous point about whether or not this is a notifiable breach, most people want to know when their data has been exposed in a fashion it wasn't intended to be and then abused for purposes like those in the forum above obviously intend to use it. Breach, not a breach, I don't care - it doesn't matter - it's my data and I want to know about it.

A Modern Breach Definition

Enough talking about all the problems, let me propose a solution. In fact, let me propose a much more modern definition of the word "breach" consistent with the real world impact of unintentionally exposed data:

A data breach occurs when information is obtained by an unauthorised party in a fashion in which it was not intended to be made available.

On this basis, the Gravatar situation was a data breach. The data wasn't meant to be accessible in this fashion ("we did not intend for the API to be used in this way"), that's why they changed the behaviour of the API once they discovered how it was being used. If everything worked as intended and data was only accessible to the right people in the right way, they wouldn't have had to "fix" anything. The reason they changed the way the service works is because - and I'm going to quote myself here - "information was obtained by an unauthorised party in a fashion in which it was not intended to be made available". And that's a breach.

https://www.troyhunt.com/when-is-a-scrape-a-breach/

Published: 2021 12 16 07:32:07

Received: 2021 12 16 07:43:32

Feed: Troy Hunt's Blog

Source: Troy Hunt's Blog

Category: Cyber Security

Topic: Cyber Security

Views: 31