Cyber Security News Aggregator

.Cyber Tzar

provide acyber security risk management

platform; including automated penetration tests and risk assesments culminating in a "cyber risk score" out of 1,000, just like a credit score.Conti Ransomware Group Diaries, Part II: The Office

published on 2022-03-02 17:49:52 UTC by BrianKrebsContent:

Earlier this week, a Ukrainian security researcher leaked almost two years’ worth of internal chat logs from Conti, one of the more rapacious and ruthless ransomware gangs in operation today. Tuesday’s story examined how Conti dealt with its own internal breaches and attacks from private security firms and governments. In Part II of this series we’ll explore what it’s like to work for Conti, as described by the Conti employees themselves.

The Conti group’s chats reveal a great deal about its internal structure and hierarchy. Conti maintains many of the same business units as a legitimate, small- to medium-sized enterprise, including a Human Resources department that is in charge of constantly interviewing potential new hires.

Other Conti departments with their own distinct budgets, staff schedules, and senior leadership include:

–Coders: Programmers hired to write malicious code, integrate disparate technologies

–Testers: Workers in charge of testing Conti malware against security tools and obfuscating it

–Administrators: Workers tasked with setting up, tearing down servers, other attack infrastructure

–Reverse Engineers: Those who can disassemble computer code, study it, find vulnerabilities or weaknesses

–Penetration Testers/Hackers: Those on the front lines battling against corporate security teams to steal data, and plant ransomware.

Conti appears to have contracted out much of its spamming operations, or at least there was no mention of “Spammers” as direct employees. Conti’s leaders seem to have set strict budgets for each of its organizational units, although it occasionally borrowed funds allocated for one department to address the pressing cashflow needs of another.

A great many of the more revealing chats concerning Conti’s structure are between “Mango” — a mid-level Conti manager to whom many other Conti employees report each day — and “Stern,” a sort of cantankerous taskmaster who can be seen constantly needling the staff for reports on their work.

In July 2021, Mango told Stern that the group was placing ads on several Russian-language cybercrime forums to hire more workers. “The salary is $2k in the announcement, but there are a lot of comments that we are recruiting galley slaves,” Mango wrote. “Of course, we dispute that and say those who work and bring results can earn more, but there are examples of coders who work normally and earn $5-$10k salary.”

The Conti chats show the gang primarily kept tabs on the victim bots infected with their malware via both the Trickbot and Emotet crimeware-as-a-service platforms, and that it employed dozens of people to continuously test, maintain and expand this infrastructure 24 hours a day, 7 days a week.

Conti members referred to Emotet as “Booz” or “Buza,” and it is evident from reading these chat logs that Buza had its own stable of more than 50 coders, and likely much of the same organizational structure as Conti.

According to Mango, as of July 18, 2021 the Conti gang employed 62 people, mostly low-level malware coders and software testers. However, Conti’s employee roster appears to have fluctuated wildly from one month to the next. For example, on multiple occasions the organization was forced to fire many employees as a security precaution in the wake of its own internal security breaches.

In May 2021, Stern told Mango he wanted his underlings to hire 100 more “encoders” to work with the group’s malware before the bulk of the gang returns from their summer vacations in Crimea. Most of these new hires, Stern says, will join the penetration testing/hacking teams headed by Conti leaders “Hof” and “Reverse.” Both Hof and Reverse appear to have direct access to the Emotet crimeware platform.

Trying to accurately gauge the size of the Conti organization is problematic, in part because cybersecurity experts have long held that Conti is merely a rebrand of another ransomware strain and affiliate program known as Ryuk. First spotted in 2018, Ryuk was just as ruthless and mercenary as Conti, and the FBI says that in the first year of its operation Ryuk earned more than $61 million in ransom payouts.

“Conti is a Targeted version of Ryuk, which comes from Trickbot and Emotet which we’ve been monitoring for some time,” researchers at Palo Alto Networks wrote about Ryuk last year. “A heavy focus was put on hospital systems, likely due to the necessity for uptime, as these systems were overwhelmed with handling the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic. We observed initial Ryuk ransom requests ranging from US$600,000 to $10 million across multiple industries.”

On May 14, 2021, Ireland’s Health Service Executive (HSE) suffered a major ransomware attack at the hands of Conti. The attack would disrupt services at several Irish hospitals, and resulted in the near complete shutdown of the HSE’s national and local networks, forcing the cancellation of many outpatient clinics and healthcare services. It took the HSE until Sept. 21, 2021 to fully restore all of its systems from the attack, at an estimated cost of more than $600 million.

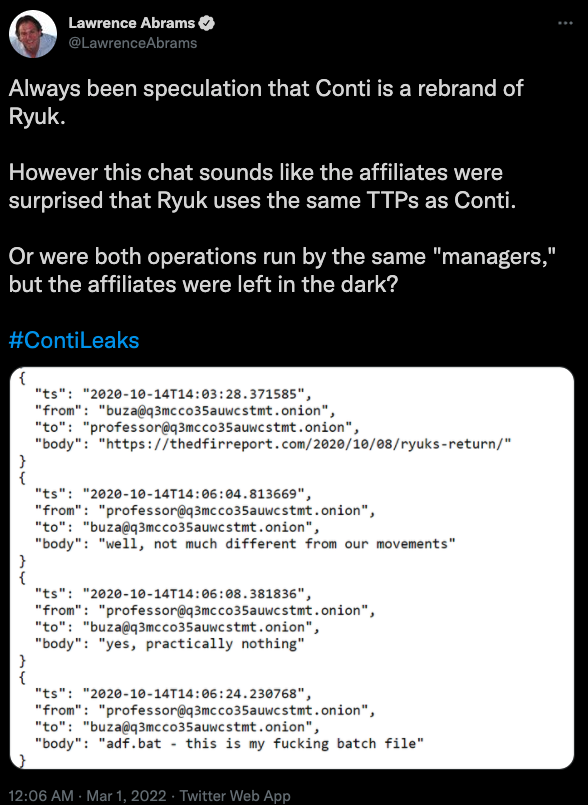

It remains unclear from reading these chats how many of Conti’s staff understood how much of the organization’s operations overlapped with that of Ryuk. Lawrence Abrams at Bleeping Computer pointed to an October 2020 Conti chat in which the Emotet representative “Buza” posts a link to a security firm’s analysis of Ryuk’s return.

“Professor,” the nickname chosen by one of Conti’s most senior generals, replies that indeed Ryuk’s tools, techniques and procedures are nearly identical to Conti’s.

“adf.bat — this is my fucking batch file,” Professor writes, evidently surprised at having read the analysis and spotting his own code being re-used in high-profile ransomware attacks by Ryuk.

“Feels like [the] same managers were running both Ryuk and Conti, with a slow migration to Conti in June 2020,” Abrams wrote on Twitter. “However, based on chats, some affiliates didn’t know that Ryuk and Conti were run by the same people.”

ATTRITION

Each Conti employee was assigned a specific 5-day workweek, and employee schedules were staggered so that some number of staff was always on hand 24/7 to address technical problems with the botnet, or to respond to ransom negotiations initiated by a victim organization.

Like countless other organizations, Conti made its payroll on the 1st and 15th of each month, albeit in the form of Bitcoin deposits. Most employees were paid $1,000 to $2,000 monthly.

However, many employees used the Conti chat room to vent about working days on end without sleep or breaks, while upper managers ignored their repeated requests for time off.

Indeed, the logs indicate that Conti struggled to maintain a steady number of programmers, testers and administrators in the face of mostly grueling and repetitive work that didn’t pay very well (particularly in relation to the earnings of the group’s top leadership). What’s more, some of the group’s top members were openly being approached to work for competing ransomware organizations, and the overall morale of the group seemed to fluctuate between paydays.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, the turnover, attrition and burnout rate was quite high for low-level Conti employees, meaning the group was forced to constantly recruit new talent.

“Our work is generally not difficult, but monotonous, doing the same thing every day,” wrote “Bentley,” the nickname chosen by the key Conti employee apparently in charge of “crypting” the group’s malware — ensuring that it goes undetected by all or at least most antivirus products on the market.

Bentley was addressing a new Conti hire — “Idgo” — telling him about his daily duties.

“Basically, this involves launching files and checking them according to the algorithm,” Bentley explains to Idgo. “Poll communication with the encoder to receive files and send reports to him. Also communication with the cryptor to send the tested assembly to the crypt. Then testing the crypt. If jambs appear at this stage , then sending reports to the cryptor and working with him. And as a result – the issuance of the finished crypt to the partner.”

Bentley cautioned that this testing of their malware had to be repeated approximately every four hours to ensure that any new malware detection capability added to Windows Defender — the built-in antivirus and security service in Windows — won’t interfere with their code.

“Approximately every 4 hours, a new update of Defender databases is released,” Bentley told Idgo. “You need to work for 8 hours before 20-21 Moscow time. And career advancement is possible.” Idgo agrees, noting that he’d started working for Conti a year earlier, as a code tester.

OBSERVATIONS

The logs show the Conti gang is exceedingly good at quickly finding many potential new ransomware victims, and the records include numerous internal debates within Conti leadership over how much certain victim companies should be forced to pay. They also show with terrifying precision how adeptly a large, organized cybercrime group can pivot from a single compromised PC to completely owning a Fortune 500 company.

As a well-staffed “big game” killing machine, Conti is perhaps unparalleled among ransomware groups. But the internal chat logs show this group is in serious need of some workflow management and tracking tools. That’s because time and time again, the Conti gang lost control over countless bots — all potential sources of ransom revenue that will help pay employee salaries for months — because of a simple oversight or mistake.

Peppered throughout the leaked Conti chats — roughly several times each week — are pleadings from various personnel in charge of maintaining the sprawling and constantly changing digital assets that support the group’s ransomware operation. These messages invariably relate to past-due invoices for multiple virtual servers, domain registrations and other cloud-based resources.

On Mar. 1, 2021, a low-level Conti employee named “Carter” says the bitcoin fund used to pay for VPN subscriptions, antivirus product licenses, new servers and domain registrations is short $1,240 in Bitcoin.

“Hello, we’re out of bitcoins, four new servers, three vpn subscriptions and 22 renewals are out,” Carter wrote on Nov. 24, 2021. “Two weeks ahead of renewals for $960 in bitcoin 0.017. Please send some bitcoins to this wallet, thanks.”

“Forgot to pay for the anchor domain, and as a result, when trying to renew it was abused and we /probably/ fucked up the bots,” Carter wrote to Stern on Sept. 23, 2020.

As part of the research for this series, KrebsOnSecurity spent many hours reading each day of Conti’s chat logs going back to September 2020. I wish I could get many of those hours back: Much of the conversations are mind-numbingly boring chit-chat and shop talk. But overall, I came away with the impression that Conti is a highly effective — if also remarkably inefficient — cybercriminal organization.

Some of Conti’s disorganized nature is probably endemic in the cybercrime industry, which is of course made up of criminals who are likely accustomed to a less regimented lifestyle. But make no mistake: As ransomware collectives like Conti continue to increase payouts from victim organizations, there will be increasing pressure on these groups to tighten up their operations and work more efficiently, professionally and profitably.

Stay tuned for Part III in this series, which will look at how Conti secured access to the cyber weaponry needed to subvert the security of their targets, as well as how the team’s leaders approached ransom negotiations with their victims.

https://krebsonsecurity.com/2022/03/conti-ransomware-group-diaries-part-ii-the-office/

Published: 2022 03 02 17:49:52

Received: 2022 03 03 16:26:04

Feed: Krebs on Security

Source: Krebs on Security

Category: Cyber Security

Topic: Cyber Security

Views: 3