Cyber Security News Aggregator

.Cyber Tzar

provide acyber security risk management

platform; including automated penetration tests and risk assesments culminating in a "cyber risk score" out of 1,000, just like a credit score.Conti Ransomware Group Diaries, Part III: Weaponry

published on 2022-03-04 20:20:29 UTC by BrianKrebsContent:

Part I of this series examined newly-leaked internal chats from the Conti ransomware group, and how the crime gang dealt with its own internal breaches. Part II explored what it’s like to be an employee of Conti’s sprawling organization. Today’s Part III looks at how Conti abused a panoply of popular commercial security services to undermine the security of their targets, as well as how the team’s leaders strategized for the upper hand in ransom negotiations with victims.

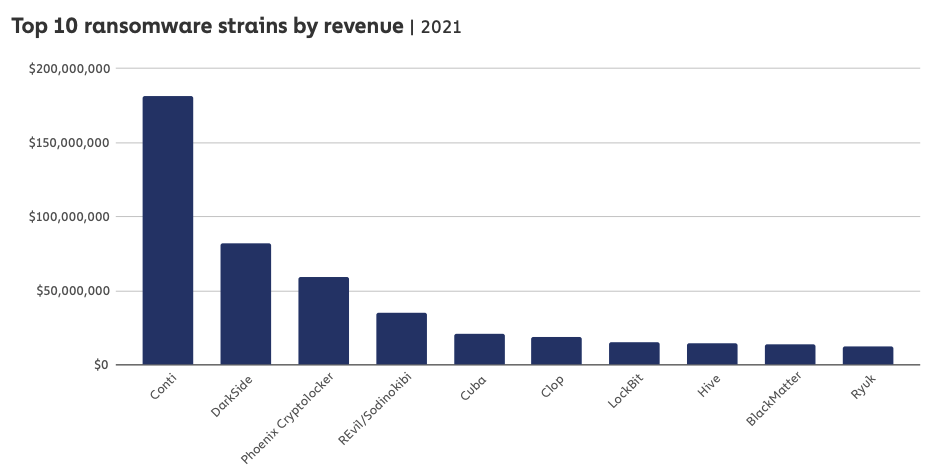

Conti is by far the most aggressive and profitable ransomware group in operation today. Image: Chainalysis

Conti is by far the most successful ransomware group in operation today, routinely pulling in multi-million dollar payments from victim organizations. That’s because more than perhaps any other ransomware outfit, Conti has chosen to focus its considerable staff and talents on targeting companies with more than $100 million in annual revenues.

As it happens, Conti itself recently joined the $100 million club. According to the latest Crypto Crime Report (PDF) published by virtual currency tracking firm Chainalysis, Conti generated at least $180 million in revenue last year.

On Feb. 27, a Ukrainian cybersecurity researcher who is currently in Ukraine leaked almost two years’ worth of internal chat records from Conti, which had just posted a press release to its victim shaming blog saying it fully supported Russia’s invasion of his country. Conti warned it would use its cyber prowess to strike back at anyone who interfered in the conflict.

The leaked chats show that the Conti group — which fluctuated in size from 65 to more than 100 employees — budgeted several thousand dollars each month to pay for a slew of security and antivirus tools. Conti sought out these tools both for continuous testing (to see how many products detected their malware as bad), but also for their own internal security.

A chat between Conti upper manager “Reshaev” and subordinate “Pin” on Aug. 8, 2021 shows Reshaev ordering Pin to quietly check on the activity of the Conti network administrators once a week — to ensure they’re not doing anything to undermine the integrity or security of the group’s operation. Reshaev tells Pin to install endpoint detection and response (EDR) tools on every administrator’s computer.

“Check admins’ activity on servers each week,” Reshaev said. “Install EDR on every computer (for example, Sentinel, Cylance, CrowdStrike); set up more complex storage system; protect LSAS dump on all computers; have only 1 active accounts; install latest security updates; install firewall on all network.”

Conti managers were hyper aware that their employees handled incredibly sensitive and invaluable data stolen from companies, information that would sell like hotcakes on the underground cybercrime forums. But in a company run by crooks, trust doesn’t come easily.

“You check on me all the time, don’t you trust me?,” asked mid-level Conti member “Bio” of “Tramp” (a.k.a. “Trump“), a top Conti overlord. Bio was handling a large bitcoin transfer from a victim ransom payment, and Bio detected that Trump was monitoring him.

“When that kind of money and people from the street come in who have never seen that kind of money, how can you trust them 1,000%?” Trump replied. “I’ve been working here for more than 15 years and haven’t seen anything else.”

OSINT

Conti also budgeted heavily for what it called “OSINT,” or open-source intelligence tools. For example, it subscribed to numerous services that can help determine who or what is behind a specific Internet Protocol (IP) address, or whether a given IP is tied to a known virtual private networking (VPN) service. On an average day, Conti had access to tens of thousands of hacked PCs, and these services helped the gang focus solely on infected systems thought to be situated within large corporate networks.

Conti’s OSINT activities also involved abusing commercial services that could help the group gain the upper hand in ransom negotiations with victims. Conti often set its ransom demands as a percentage of a victim’s annual revenues, and the gang was known to harass board members of and investors in companies that refused to engage or negotiate.

In October 2021, Conti underling “Bloodrush” told his manager “Bentley” that the group urgently needed to purchase subscriptions to Crunchbase Pro and Zoominfo, noting that the services provide detailed information on millions of companies, such as how much insurance a company maintains; their latest earnings estimates; and contact information of executive officers and board members.

In a months-long project last year, Conti invested $60,000 in acquiring a valid license to Cobalt Strike, a commercial network penetration testing and reconnaissance tool that is sold only to vetted partners. But stolen or ill-gotten “Coba” licenses are frequently abused by cybercriminal gangs to help lay the groundwork for the installation of ransomware on a victim network. It appears $30,000 of that investment went to cover the actual cost of a Cobalt Strike license, while the other half was paid to a legitimate company that secretly purchased the license on Conti’s behalf.

Likewise, Conti’s Human Resources Department budgeted thousands of dollars each month toward employer subscriptions to numerous job-hunting websites, where Conti HR employees would sift through resumes for potential hires. In a note to Conti taskmaster “Stern” explaining the group’s paid access on one employment platform, Conti HR employee “Salamandra” says their workers have already viewed 25-30 percent of all relevant CVs available on the platform.

“About 25% of resumes will be free for you, as they are already opened by other managers of our company some CVs are already open for you, over time their number will be 30-35%,” Salamandra wrote. “Out of 10 CVs, approximately 3 will already be available.”

Another organizational unit within Conti with its own budget allocations — called the “Reversers” — was responsible for finding and exploiting new security vulnerabilities in widely used hardware, software and cloud-based services. On July 7, 2021, Stern ordered reverser “Kaktus” to start focusing the department’s attention on Windows 11, Microsoft’s newest operating system.

“Win11 is coming out soon, we should be ready for this and start studying it,” Stern said. “The beta is already online, you can officially download and work.”

BY HOOK OR BY CROOK

The chats from the Conti organization include numerous internal deliberations over how much different ransomware victims should be made to pay. And on this front, Conti appears to have sought assistance from multiple third parties.

Milwaukee-based cyber intelligence firm Hold Security this week posted a screenshot on Twitter of a conversation in which one Conti member claims to have a journalist on their payroll who can be hired to write articles that put pressure on victim companies to pay a ransom demand.

“There is a journalist who will help intimidate them for 5 percent of the payout,” wrote Conti member “Alarm,” on March 30, 2021.

The Conti team also had decent working relationships with multiple people who worked at companies that helped ransomware victims navigate paying an extortion demand in virtual currency. One friendly negotiator even had his own nickname within the group — “The Spaniard” — who according to Conti mid-level manager Mango is a Romanian man who works for a large ransomware recovery firm in Canada.

“We have a partner here in the same panel who has been working with this negotiator for a long time, like you can quickly negotiate,” Trump says to Bio on Dec. 12, 2021, in regards to their ransomware negotiations with LeMans Corp., a large Wisconsin-based distributor of powersports equipment [LeMans declined to comment for this story].

Trump soon after posts a response from their negotiator friend:

“They are willing to pay $1KK [$1 million] quickly. Need decryptors. The board is willing to go to a maximum of $1KK, which is what I provided to you. Hopefully, they will understand. The company revenue is under $100KK [$100 million]. This is not a large organization. Let me know what you can do. But if you have information about their cyber insurance and maybe they have a lot of money in their account, I need a bank payout, then I can bargain. I’ll be online by 21-00 Moscow time. For now, take a look at the documents and see if there is insurance and bank statements.”

In a different ransom discussion, the negotiator urges Conti to reconsider such a hefty demand.

“My client only has a max of $200,000 to pay and only wants the data,” the negotiator wrote on Oct. 7, 2021. “See what you can do or this deal will not happen.”

Many organizations now hold cyber insurance to cover the losses associated with a ransomware attack. The logs indicate Conti was ambivalent about working with these victims. For one thing, the insurers seemed to limit their ability to demand astronomical ransom amounts. On the other hand, insured victims usually paid out, with a minimum of hassle or protracted back-and-forth negotiations.

“They are insured for cyber risks, so what are we waiting for?” asks Conti upper manager “Revers,” in a conversation on Sept. 14, 2021.

“There will be trades with the insurance company?” asks Conti employee “Grant.”

“That’s not how it works,” Revers replied. “They have a coverage budget. We just take it and that’s it.”

Conti was an early adopter of the ransomware best practice of “double extortion,” which involves charging the victim two separate ransom demands: One in exchange for a digital key needed to unlock infected systems, and another to secure a promise that any stolen data will not be published or sold, and will be destroyed. Indeed, some variation of the message “need decryptors, deletion logs” can be seen throughout the chats following the gang’s receipt of payment from a victim.

Conti victims were directed to a page on the dark web that included a countdown timer. Victims who failed to negotiate a payment before the timer expired could expect to see their internal data automatically published on Conti’s victim shaming blog.

The beauty of the double extortion approach is that even when victims refuse to pay for a decryption key — perhaps because they’re confident they can restore systems from backups — they might still pay to keep the breach quiet.

“Hello [victim company redacted],” the gang wrote in January 2022. “We are Conti Group. We want to inform that your company local network have been hacked and encrypted. We downloaded from your network more than 180GB of sensitive data. – Shared HR – Shared_Accounting – Corporate Debt – Departments. You can see your page in the our blog here [dark web link]. Your page is hidden. But it will be published if you do not go to the negotiations.”

“We came to an agreement before the New Year,” Conti member “Skippy” wrote later in a message to the victim company. “You got a lot of time, more than enough to find any sum and fulfill your part of this agreement. However, you now ask for additional time, additional proofs, etc. Seems like you are preparing to break the agreement and flee, or just to decrease the sum. Moreover, it is a very strange request and explanation. A lot of companies pay such amounts without any problems. So, our answer: We are waiting for the above mentioned sum until 5 February. We keep our words. If we see no payment and you continue to add any conditions, we begin to upload data. That is all.”

And a reputation for keeping their word is what makes groups like Conti so feared. But some may come to question the group’s competence, and whether it may now be too risky to work with them.

On Mar. 3, a new Twitter account called “Trickbotleaks” began posting the names, photos and personal information of what the account claimed were top Trickbot administrators, including information on many of the Conti nicknames mentioned throughout this story. The Trickbotleaks Twitter account was suspended less than 24 hours later.

On Mar. 2, the Twitter account that originally leaked the Conti chat (a.k.a. “jabber”) records posted fresh logs from the Conti chat room, proving the infiltrator still had access and that Conti hadn’t figured out how they’d been had.

“Ukraine will rise!,” the account tweeted. “Fresh jabber logs.”

https://krebsonsecurity.com/2022/03/conti-ransomware-group-diaries-part-iii-weaponry/

Published: 2022 03 04 20:20:29

Received: 2022 03 04 20:26:03

Feed: Krebs on Security

Source: Krebs on Security

Category: Cyber Security

Topic: Cyber Security

Views: 13