Cyber Security News Aggregator

.Cyber Tzar

provide acyber security risk management

platform; including automated penetration tests and risk assesments culminating in a "cyber risk score" out of 1,000, just like a credit score.Conti Ransomware Group Diaries, Part I: Evasion

published on 2022-03-01 20:50:30 UTC by BrianKrebsContent:

A Ukrainian security researcher this week leaked several years of internal chat logs and other sensitive data tied to Conti, an aggressive and ruthless Russian cybercrime group that focuses on deploying its ransomware to companies with more than $100 million in annual revenue. The chat logs offer a fascinating glimpse into the challenges of running a sprawling criminal enterprise with more than 100 salaried employees. The records also provide insight into how Conti has dealt with its own internal breaches and attacks from private security firms and foreign governments.

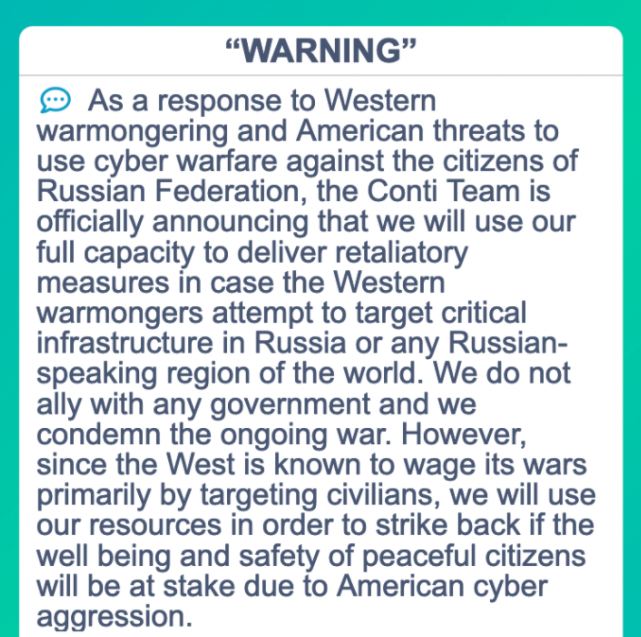

Conti’s threatening message this week regarding international interference in Ukraine.

Conti makes international news headlines each week when it publishes to its dark web blog new information stolen from ransomware victims who refuse to pay an extortion demand. In response to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, Conti published a statement announcing its “full support.”

“If anybody will decide to organize a cyberattack or any war activities against Russia, we are going to use all our possible resources to strike back at the critical infrastructures of an enemy,” the Conti blog post read.

On Sunday, Feb. 27, a new Twitter account “Contileaks” posted links to an archive of chat messages taken from Conti’s private communications infrastructure, dating from January 29, 2021 to the present day. Shouting “Glory for Ukraine,” the Contileaks account has since published additional Conti employee conversations from June 22, 2020 to Nov. 16, 2020.

The Contileaks account did not respond to requests for comment. But Alex Holden, the Ukrainian-born founder of the Milwaukee-based cyber intelligence firm Hold Security, said the person who leaked the information is not a former Conti affiliate — as many on Twitter have assumed. Rather, he said, the leaker is a Ukrainian security researcher who has chosen to stay in his country and fight.

“The person releasing this is a Ukrainian and a patriot,” Holden said. “He’s seeing that Conti is supporting Russia in its invasion of Ukraine, and this is his way to stop them in his mind at least.”

GAP #1

The temporal gaps in these chat records roughly correspond to times when Conti’s IT infrastructure was dismantled and/or infiltrated by security researchers, private companies, law enforcement, and national intelligence agencies. The holes in the chat logs also match up with periods of relative quiescence from the group, as it sought to re-establish its network of infected systems and dismiss its low-level staff as a security precaution.

On Sept. 22, 2020, the U.S. National Security Agency (NSA) began a weeks-long operation in which it seized control over the Trickbot botnet, a malware crime machine that has infected millions of computers and is often used to spread ransomware. Conti is one of several cybercrime groups that has regularly used Trickbot to deploy malware.

Once in control over Trickbot, the NSA’s hackers sent all infected systems a command telling them to disconnect themselves from the Internet servers the Trickbot overlords used to control compromised Microsoft Windows computers. On top of that, the NSA stuffed millions of bogus records about new victims into the Trickbot database.

News of the Trickbot compromise was first published here on Oct. 2, 2020, but the leaked Conti chats show that the group’s core leadership detected something was seriously wrong with their crime machine just a few hours after the initial compromise of Trickbot’s infrastructure on Sept. 22.

“The one who made this garbage did it very well,” wrote “Hof,” the handle chosen by a top Conti leader, commenting on the Trickbot malware implant that was supplied by the NSA and quickly spread to the rest of the botnet. “He knew how the bot works, i.e. he probably saw the source code, or reversed it. Plus, he somehow encrypted the config, i.e. he had an encoder and a private key, plus uploaded it all to the admin panel. It’s just some kind of sabotage.”

“Moreover, the bots have been flooded with such a config that they will simply work idle,” Hof explained to his team on Sept. 23, 2020. Hof noted that the intruder even kneecapped Trickbot’s built-in failsafe recovery mechanism. Trickbot was configured so that if none of the botnet’s control servers were reachable, the bots could still be recaptured and controlled by registering a pre-computed domain name on EmerDNS, a decentralized domain name system based on the Emercoin virtual currency.

“After a while they will download a new config via emercoin, but they will not be able to apply this config, because this saboteur has uploaded the config with the maximum [version] number, and the bot is checking that the new config [version number] should be larger than the old one,” Hof wrote. “Sorry, but this is fucked up. I don’t know how to get them back.”

It would take the Conti gang several weeks to rebuild its malware infrastructure, and infect tens of thousands of new Microsoft Windows systems. By late October 2020, Conti’s network of infected systems had grown to include 428 medical facilities throughout the United States. The gang’s leaders saw an opportunity to create widespread panic — if not also chaos — by deploying their ransomware simultaneously to hundreds of American healthcare organizations already struggling amid a worldwide pandemic.

“Fuck the clinics in the USA this week,” wrote Conti manager “Target” on Oct. 26, 2020. “There will be panic. 428 hospitals.”

On October 28, the FBI and the U.S. Department of Homeland Security hastily assembled a conference call with healthcare industry executives warning about an “imminent cybercrime threat to U.S. hospitals and healthcare providers.”

Follow-up reporting confirmed that at least a dozen healthcare organizations were hit with ransomware that week, but the carnage apparently was not much worse than a typical week in the healthcare sector. One information security leader in the healthcare industry told KrebsOnSecurity at the time that it wasn’t uncommon for the industry to see at least one hospital or health care facility hit with ransomware each day.

GAP #2

The more recent gap in the Conti chat logs corresponds to a Jan. 26, 2021 international law enforcement operation to seize control of Emotet, a prolific malware strain and cybercrime-as-a-service platform that was used heavily by Conti. Following the Emotet takedown, the Conti group once again reorganized, with everyone forced to pick new nicknames and passwords.

The logs show Conti made a special effort to help one of its older members — Alla Witte — a 55-year-old Latvian woman arrested last year on suspicion of working as a programmer for the Trickbot group. The chat records indicate Witte became something of a maternal figure for many of Conti’s younger personnel, and after her arrest Conti’s leadership began scheming a way to pay for her legal defense.

Alla Witte’s personal website — allawitte[.]nl — circa October 2018.

“They gave me a lawyer, they said the best one, plus excellent connections, he knows the investigator, he knows the judge, he is a federal lawyer there, licensed, etc., etc.,” wrote “Mango” — a mid-level manager within Conti — to “Stern,” a much higher-up Conti taskmaster who frequently asked various units of the gang for updates on their daily assignments.

Stern agreed that this was the best course of action, but it’s unclear if it was successfully carried out. Also, the entire scheme may not have been as altruistic as it seemed: Mango suggested that paying Witte’s attorney fees might also give the group inside access to information about the government’s ongoing investigation of Trickbot.

“Let’s try to find a way to her lawyer right now and offer him to directly sell the data bypassing her,” Mango suggests to Stern on June 23, 2021.

The FBI has been investigating Trickbot for years, and it is clear that at some point the U.S. government shared information with the Russians about the hackers they suspected were behind Trickbot. It is also clear from reading these logs that the Russians did little with this information until October 2021, when Conti’s top generals began receiving tips from their Russian law enforcement sources that the investigation was being rekindled.

“Our old case was resumed,” wrote the Conti member “Kagas” in a message to Stern on Oct. 6, 2021. “The investigator said why it was resumed: The Americans officially requested information about Russian hackers, not only about us, but in general who was caught around the country. Actually, they are interested in the Trickbot, and some other viruses. Next Tuesday, the investigator called us for a conversation, but for now, it’s like [we’re being called on as] witnesses. That way if the case is suspended, they can’t interrogate us in any way, and, in fact, because of this, they resumed it. We have already contacted our lawyers.”

Incredibly, another Conti member pipes into the discussion and says the group has been assured that the investigation will go nowhere from the Russian side, and that the entire inquiry from local investigators would be closed by mid-November 2021.

It appears Russian investigators were more interested in going after a top Conti competitor — REvil, an equally ruthless Russian ransomware group that likewise mainly targeted large organizations that could pay large ransom demands.

On Jan. 14, 2022, the Russian government announced the arrest of 14 people accused of working for REvil. The Russian Federal Security Service (FSB) said the actions were taken in response to a request from U.S. officials, but many experts believe the crackdown was part of a cynical ploy to assuage (or distract) public concerns over Russian President Vladimir Putin’s bellicose actions in the weeks before his invasion of Ukraine.

The leaked Conti messages show that TrickBot was effectively shut down earlier this month. As Catalin Cimpanu at The Record points out, the messages also contain copious ransom negotiations and payments from companies that had not disclosed a breach or ransomware incident (and indeed had paid Conti to ensure their silence). In addition, there are hundreds of bitcoin addresses in these chats that will no doubt prove useful to law enforcement organizations seeking to track the group’s profits.

If you enjoyed this story, please consider reading Part II: The Office, which is about what it’s like to work for Conti, told through the private messages exchanged by Conti employees working in different operational units. Part III: Weaponry looks at how Conti abused a panoply of popular commercial security services to undermine the security of their targets, as well as how the team’s leaders strategized for the upper hand in ransom negotiations with victims. Part IV: Cryptocrime examines different schemes Conti pursued to invest in and steal cryptocurrencies.

https://krebsonsecurity.com/2022/03/conti-ransomware-group-diaries-part-i-evasion/

Published: 2022 03 01 20:50:30

Received: 2022 03 08 14:26:47

Feed: Krebs on Security

Source: Krebs on Security

Category: Cyber Security

Topic: Cyber Security

Views: 8