Cyber Security News Aggregator

.Cyber Tzar

provide acyber security risk management

platform; including automated penetration tests and risk assesments culminating in a "cyber risk score" out of 1,000, just like a credit score.DEA Investigating Breach of Law Enforcement Data Portal

published on 2022-05-12 11:00:30 UTC by BrianKrebsContent:

The U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) says it is investigating reports that hackers gained unauthorized access to an agency portal that taps into 16 different federal law enforcement databases. KrebsOnSecurity has learned the alleged compromise is tied to a cybercrime and online harassment community that routinely impersonates police and government officials to harvest personal information on their targets.

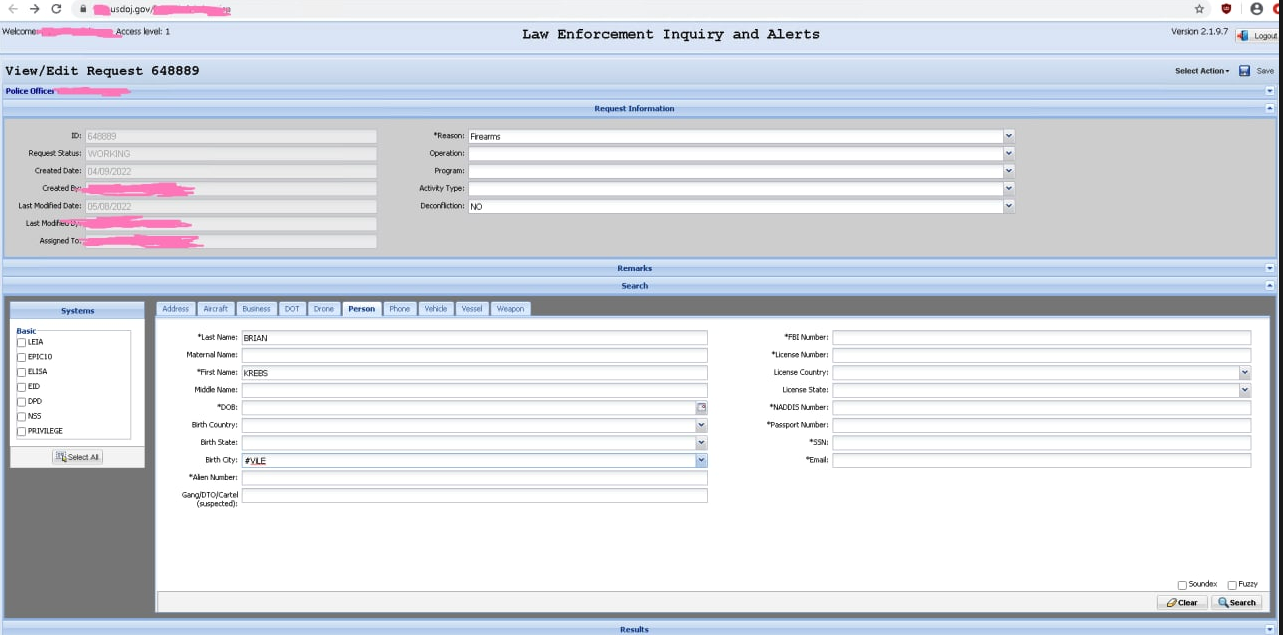

Unidentified hackers shared this screenshot of alleged access to the Drug Enforcement Administration’s intelligence sharing portal.

On May 8, KrebsOnSecurity received a tip that hackers obtained a username and password for an authorized user of esp.usdoj.gov, which is the Law Enforcement Inquiry and Alerts (LEIA) system managed by the DEA.

KrebsOnSecurity shared information about the allegedly hijacked account with the DEA, the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI), and the Department of Justice, which houses both agencies. The DEA declined to comment on the validity of the claims, issuing only a brief statement in response.

“DEA takes cyber security and information of intrusions seriously and investigates all such reports to the fullest extent,” the agency said in a statement shared via email.

According to this page at the Justice Department website, LEIA “provides federated search capabilities for both EPIC and external database repositories,” including data classified as “law enforcement sensitive” and “mission sensitive” to the DEA.

A document published by the Obama administration in May 2016 (PDF) says the DEA’s El Paso Intelligence Center (EPIC) systems in Texas are available for use by federal, state, local and tribal law enforcement, as well as the Department of Defense and intelligence community.

EPIC and LEIA also have access to the DEA’s National Seizure System (NSS), which the DEA uses to identify property thought to have been purchased with the proceeds of criminal activity (think fancy cars, boats and homes seized from drug kingpins).

“The EPIC System Portal (ESP) enables vetted users to remotely and securely share intelligence, access the National Seizure System, conduct data analytics, and obtain information in support of criminal investigations or law enforcement operations,” the 2016 White House document reads. “Law Enforcement Inquiry and Alerts (LEIA) allows for a federated search of 16 Federal law enforcement databases.”

The screenshots shared with this author indicate the hackers could use EPIC to look up a variety of records, including those for motor vehicles, boats, firearms, aircraft, and even drones.

Claims about the purloined DEA access were shared with this author by “KT,” the current administrator of the Doxbin — a highly toxic online community that provides a forum for digging up personal information on people and posting it publicly.

As KrebsOnSecurity reported earlier this year, the previous owner of the Doxbin has been identified as the leader of LAPSUS$, a data extortion group that hacked into some of the world’s largest tech companies this year — including Microsoft, NVIDIA, Okta, Samsung and T-Mobile.

That reporting also showed how the core members of LAPSUS$ were involved in selling a service offering fraudulent Emergency Data Requests (EDRs), wherein the hackers use compromised police and government email accounts to file warrantless data requests with social media firms, mobile telephony providers and other technology firms, attesting that the information being requested can’t wait for a warrant because it relates to an urgent matter of life and death.

From the standpoint of individuals involved in filing these phony EDRs, access to databases and user accounts within the Department of Justice would be a major coup. But the data in EPIC would probably be far more valuable to organized crime rings or drug cartels, said Nicholas Weaver, a researcher for the International Computer Science Institute at University of California, Berkeley.

Weaver said it’s clear from the screenshots shared by the hackers that they could use their access not only to view sensitive information, but also submit false records to law enforcement and intelligence agency databases.

“I don’t think these [people] realize what they got, how much money the cartels would pay for access to this,” Weaver said. “Especially because as a cartel you don’t search for yourself you search for your enemies, so that even if it’s discovered there is no loss to you of putting things ONTO the DEA’s radar.”

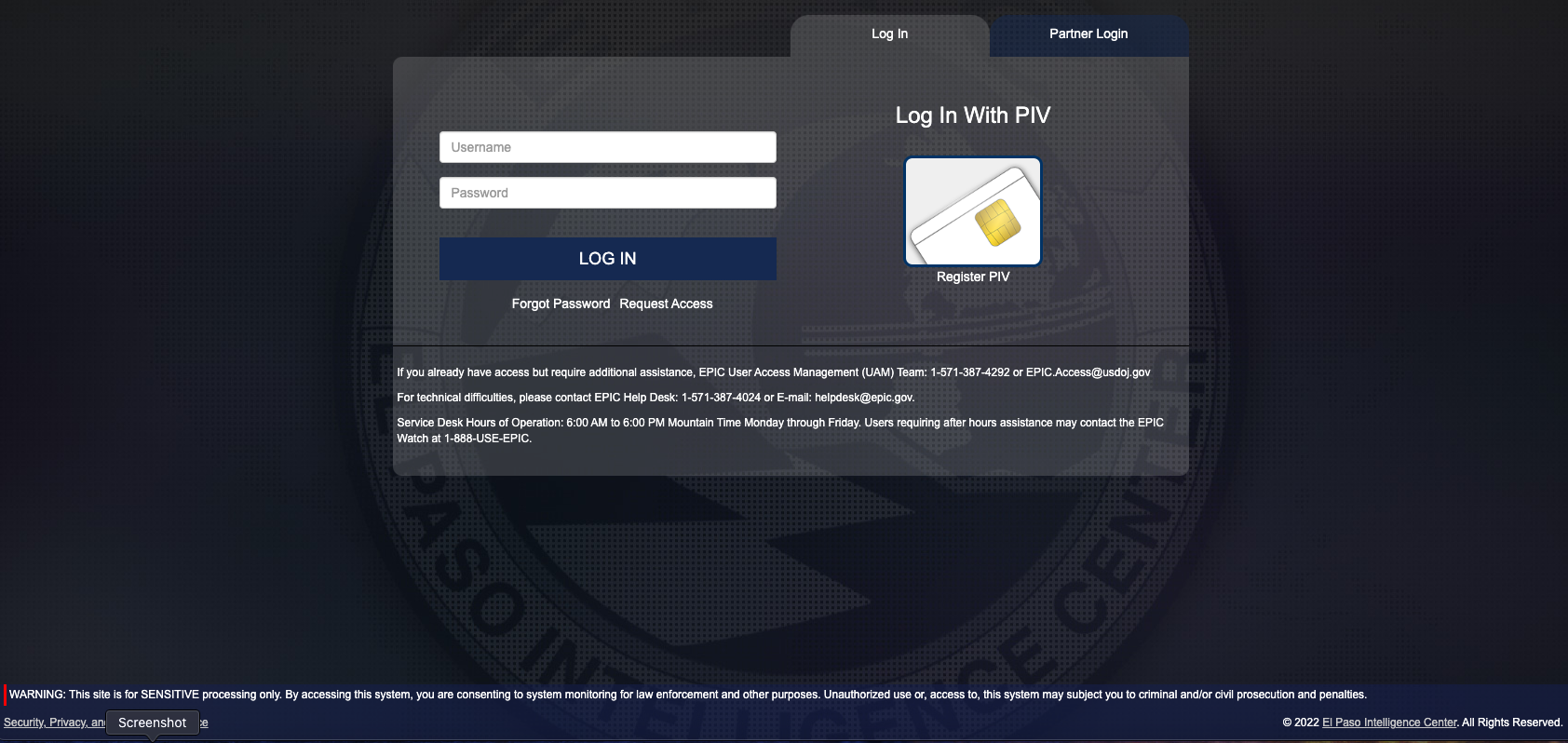

The DEA’s EPIC portal login page.

ANALYSIS

The login page for esp.usdoj.gov (above) suggests that authorized users can access the site using a “Personal Identity Verification” or PIV card, which is a fairly strong form of authentication used government-wide to control access to federal facilities and information systems at each user’s appropriate security level.

However, the EPIC portal also appears to accept just a username and password, which would seem to radically diminish the security value of requiring users to present (or prove possession of) an authorized PIV card. Indeed, KT said the hacker who obtained this illicit access was able to log in using the stolen credentials alone, and that at no time did the portal prompt for a second authentication factor.

It’s not clear why there are still sensitive government databases being protected by nothing more than a username and password, but I’m willing to bet big money that this DEA portal is not only offender here. The DEA portal esp.usdoj.gov is listed on Page 87 of a Justice Department “data inventory,” which catalogs all of the data repositories that correspond to DOJ agencies.

There are 3,330 results. Granted, only some of those results are login portals, but that’s just within the Department of Justice.

If we assume for the moment that state-sponsored foreign hacking groups can gain access to sensitive government intelligence in the same way as teenage hacker groups like LAPSUS$, then it is long past time for the U.S. federal government to perform a top-to-bottom review of authentication requirements tied to any government portals that traffic in sensitive or privileged information.

I’ll say it because it needs to be said: The United States government is in urgent need of leadership on cybersecurity at the executive branch level — preferably someone who has the authority and political will to eventually disconnect any federal government agency data portals that fail to enforce strong, multi-factor authentication.

I realize this may be far more complex than it sounds, particularly when it comes to authenticating law enforcement personnel who access these systems without the benefit of a PIV card or government-issued device (state and local authorities, for example). It’s not going to be as simple as just turning on multi-factor authentication for every user, thanks in part to a broad diversity of technologies being used across the law enforcement landscape.

But when hackers can plunder 16 law enforcement databases, arbitrarily send out law enforcement alerts for specific people or vehicles, or potentially disrupt ongoing law enforcement operations — all because someone stole, found or bought a username and password — it’s time for drastic measures.

https://krebsonsecurity.com/2022/05/dea-investigating-breach-of-law-enforcement-data-portal/

Published: 2022 05 12 11:00:30

Received: 2022 05 18 01:26:37

Feed: Krebs on Security

Source: Krebs on Security

Category: Cyber Security

Topic: Cyber Security

Views: 14