Cyber Security News Aggregator

.Cyber Tzar

provide acyber security risk management

platform; including automated penetration tests and risk assesments culminating in a "cyber risk score" out of 1,000, just like a credit score.U.S. Govt. Apps Bundled Russian Code With Ties to Mobile Malware Developer

published on 2022-11-28 22:08:21 UTC by BrianKrebsContent:

A recent scoop by Reuters revealed that mobile apps for the U.S. Army and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) were integrating software that sends visitor data to a Russian company called Pushwoosh, which claims to be based in the United States. But that story omitted an important historical detail about Pushwoosh: In 2013, one of its developers admitted to authoring the Pincer Trojan, malware designed to surreptitiously intercept and forward text messages from Android mobile devices.

Pushwoosh says it is a U.S. based company that provides code for software developers to profile smartphone app users based on their online activity, allowing them to send tailor-made notifications. But a recent investigation by Reuters raised questions about the company’s real location and truthfulness.

The Army told Reuters it removed an app containing Pushwoosh in March, citing “security concerns.” The Army app was used by soldiers at one of the nation’s main combat training bases.

Reuters said the CDC likewise recently removed Pushwoosh code from its app over security concerns, after reporters informed the agency Pushwoosh was not based in the Washington D.C. area — as the company had represented — but was instead operated from Novosibirsk, Russia.

Pushwoosh’s software also was found in apps for “a wide array of international companies, influential nonprofits and government agencies from global consumer goods company Unilever and the Union of European Football Associations (UEFA) to the politically powerful U.S. gun lobby, the National Rifle Association (NRA), and Britain’s Labour Party.”

The company’s founder Max Konev told Reuters Pushwoosh “has no connection with the Russian government of any kind” and that it stores its data in the United States and Germany.

But Reuters found that while Pushwoosh’s social media and U.S. regulatory filings present it as a U.S. company based variously in California, Maryland and Washington, D.C., the company’s employees are located in Novosibirsk, Russia.

Reuters also learned that the company’s address in California does not exist, and that two LinkedIn accounts for Pushwoosh employees in Washington, D.C. were fake.

“Pushwoosh never mentioned it was Russian-based in eight annual filings in the U.S. state of Delaware, where it is registered, an omission which could violate state law,” Reuters reported.

Pushwoosh admitted the LinkedIn profiles were fake, but said they were created by a marketing firm to drum up business for the company — not misrepresent its location.

Pushwoosh told Reuters it used addresses in the Washington, D.C. area to “receive business correspondence” during the coronavirus pandemic. A review of the Pushwoosh founder’s online presence via Constella Intelligence shows his Pushwoosh email address was tied to a phone number in Washington, D.C. that was also connected to email addresses and account profiles for over a dozen other Pushwoosh employees.

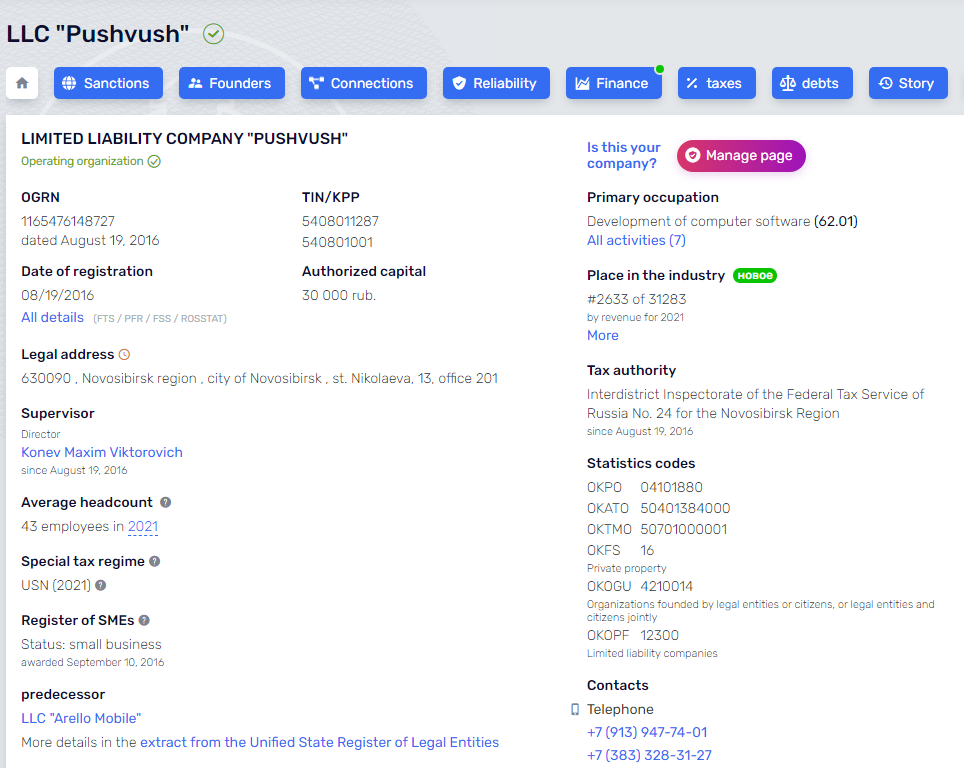

Pushwoosh was incorporated in Novosibirsk, Russia in 2016.

THE PINCER TROJAN CONNECTION

The dust-up over Pushwoosh came in part from data gathered by Zach Edwards, a security researcher who until recently worked for the Internet Safety Labs, a nonprofit organization that funds research into online threats.

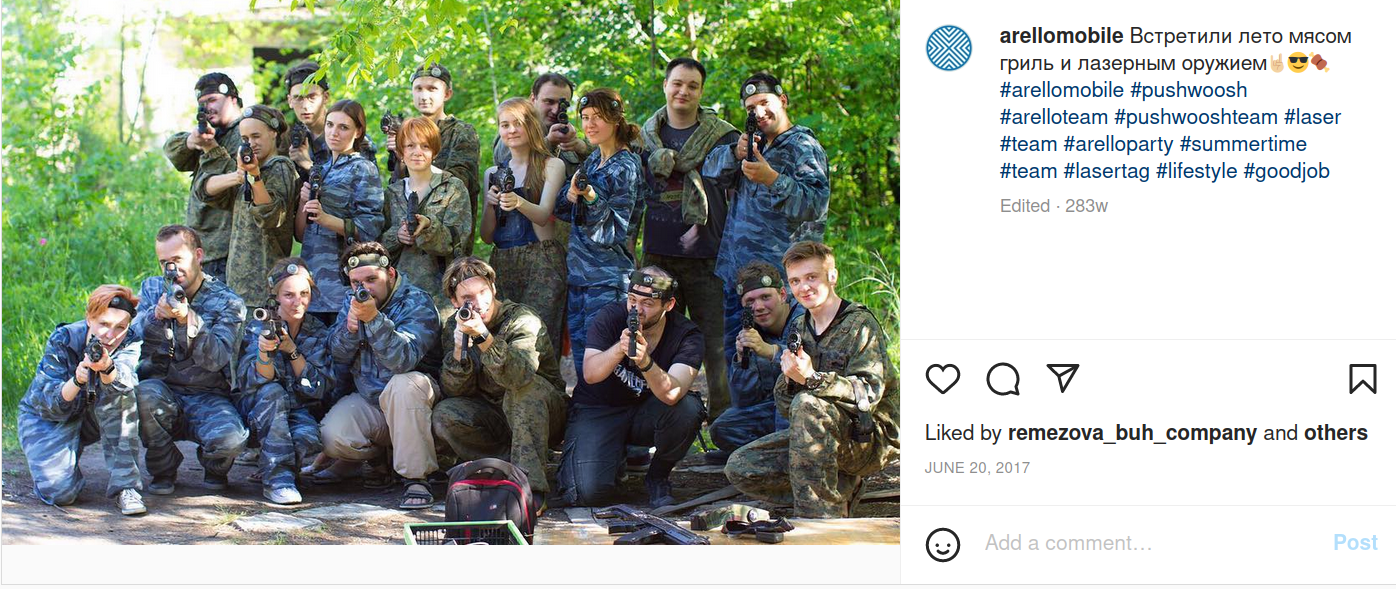

Edwards said Pushwoosh began as Arello-Mobile, and for several years the two co-branded — appearing side by side at various technology expos. Around 2016, he said, the two companies both started using the Pushwoosh name.

A search on Pushwoosh’s code base shows that one of the company’s longtime developers is a 41-year-old from Novosibirsk named Yuri Shmakov. In 2013, KrebsOnSecurity interviewed Shmakov for the story, “Who Wrote the Pincer Android Trojan?” wherein Shmakov acknowledged writing the malware as a freelance project.

Shmakov told me that, based on the client’s specifications, he suspected it might ultimately be put to nefarious uses. Even so, he completed the job and signed his work by including his nickname in the app’s code.

“I was working on this app for some months, and I was hoping that it would be really helpful,” Shmakov wrote. “[The] idea of this app is that you can set it up as a spam filter…block some calls and SMS remotely, from a Web service. I hoped that this will be [some kind of] blacklist, with logging about blocked [messages/calls]. But of course, I understood that client [did] not really want this.”

Shmakov did not respond to requests for comment. His LinkedIn profile says he stopped working for Arello Mobile in 2016, and that he currently is employed full-time as the Android team leader at an online betting company.

In a blog post responding to the Reuters story, Pushwoosh said it is a privately held company incorporated under the state laws of Delaware, USA, and that Pushwoosh Inc. was never owned by any company registered in the Russian Federation.

“Pushwoosh Inc. used to outsource development parts of the product to the Russian company in Novosibirsk, mentioned in the article,” the company said. “However, in February 2022, Pushwoosh Inc. terminated the contract.”

However, Edwards noted that dozens of developer subdomains on Pushwoosh’s main domain still point to JSC Avantel, an Internet provider based in Novosibirsk, Russia.

WAR GAMES

Edwards said the U.S. Army’s app had a custom Pushwoosh configuration that did not appear on any other customer implementation.

“It had an extremely custom setup that existed nowhere else,” Edwards said. “Originally, it was an in-app Web browser, where it integrated a Pushwoosh javascript so that any time a user clicked on links, data went out to Pushwoosh and they could push back whatever they wanted through the in-app browser.”

An Army Times article published the day after the Reuters story ran said at least 1,000 people downloaded the app, which “delivered updates for troops at the National Training Center on Fort Irwin, Calif., a critical waypoint for deploying units to test their battlefield prowess before heading overseas.”

In April 2022, roughly 4,500 Army personnel converged on the National Training Center for a war games exercise on how to use lessons learned from Russia’s war against Ukraine to prepare for future fights against a major adversary such as Russia or China.

Edwards said despite Pushwoosh’s many prevarications, the company’s software doesn’t appear to have done anything untoward to its customers or users.

“Nothing they did has been seen to be malicious,” he said. “Other than completely lying about where they are, where their data is being hosted, and where they have infrastructure.”

GOV 311

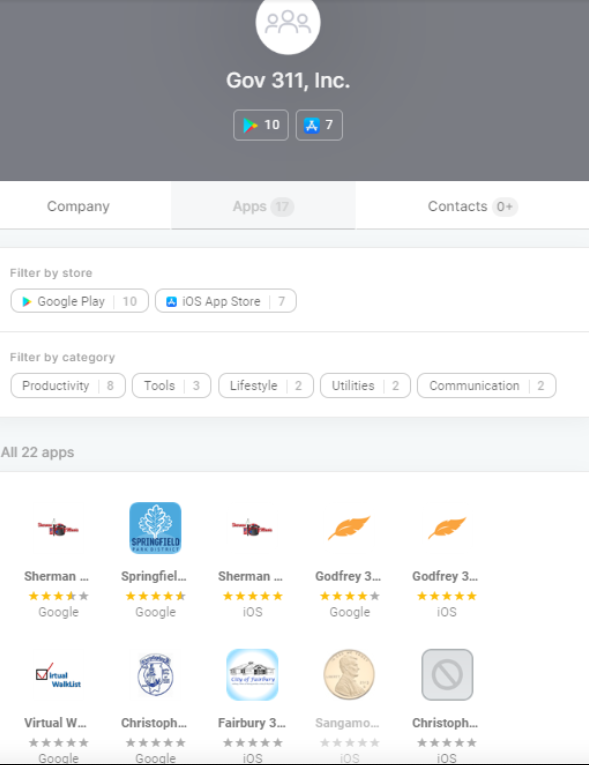

Edwards also found Pushwoosh’s technology embedded in nearly two dozen mobile apps that were sold to cities and towns across Illinois as a way to help citizens access general information about their local communities and officials.

The Illinois apps that bundled Pushwoosh’s technology were produced by a company called Government 311, which is owned by Bill McCarty, the current director of the Springfield Office of Budget and Management. A 2014 story in The State Journal-Register said Gov 311’s pricing was based on population, and that the app would cost around $2,500 per year for a city with approximately 25,000 people.

The Illinois apps that bundled Pushwoosh’s technology were produced by a company called Government 311, which is owned by Bill McCarty, the current director of the Springfield Office of Budget and Management. A 2014 story in The State Journal-Register said Gov 311’s pricing was based on population, and that the app would cost around $2,500 per year for a city with approximately 25,000 people.

McCarty told KrebsOnSecurity that his company stopped using Pushwoosh “years ago,” and that it now relies on its own technology to provide push notifications through its 311 apps.

But Edwards found some of the 311 apps still try to phone home to Pushwoosh, such as the 311 app for Riverton, Ill.

“Riverton ceased being a client several years ago, which [is] probably why their app was never updated to change out Pushwoosh,” McCarty explained. “We are in the process of updating all client apps and a website refresh. As part of that, old unused apps like Riverton 311 will be deleted.”

FOREIGN ADTECH THREAT?

Edwards said it’s far from clear how many other state and local government apps and Web sites rely on technology that sends user data to U.S. adversaries overseas. In July, Congress introduced an amended version of the Intelligence Authorization Act for 2023, which included a new section focusing on data drawn from online ad auctions that could be used to geolocate individuals or gain other information about them.

Business Insider reports that if this section makes it into the final version — which the Senate also has to pass — the Office for the Director of National Intelligence (ODNI) will have 60 days after the Act becomes law to produce a risk assessment. The assessment will look into “the counterintelligence risks of, and the exposure of intelligence community personnel to, tracking by foreign adversaries through advertising technology data,” the Act states.

Edwards says he’s hoping those changes pass, because what he found with Pushwoosh is likely just a drop in a bucket.

“I’m hoping that Congress acts on that,” he said. “If they were to put a requirement that there’s an annual audit of risks from foreign ad tech, that would at least force people to identify and document those connections.”

https://krebsonsecurity.com/2022/11/u-s-govt-apps-bundled-russian-code-with-ties-to-mobile-malware-developer/

Published: 2022 11 28 22:08:21

Received: 2022 12 01 19:39:47

Feed: Krebs on Security

Source: Krebs on Security

Category: Cyber Security

Topic: Cyber Security

Views: 27