Cyber Security News Aggregator

.Cyber Tzar

provide acyber security risk management

platform; including automated penetration tests and risk assesments culminating in a "cyber risk score" out of 1,000, just like a credit score.Operation Endgame

published on 2024-05-30 04:25:59 UTC by Troy HuntContent:

Today we loaded 16.5M email addresses and 13.5M unique passwords provided by law enforcement agencies into Have I Been Pwned (HIBP) following botnet takedowns in a campaign they've coined Operation Endgame. That link provides an excellent overview so start there then come back to this blog post which adds some insight into the data and explains how HIBP fits into the picture.

Since 2013 when I kicked off HIBP as a pet project, it has become an increasingly important part of the security posture of individuals, organisations, governments and law enforcement agencies. Gradually and organically, it has found a fit where it's able to provide a useful service to the good guys after the bad guys have done evil cyber things. The phrase I've been fond of this last decade is that HIBP is there to do good things with data after bad things happen. The reputation and reach the service has gained in this time has led to partnerships such as the one you're reading about here today. So, with that in mind, let's get into the mechanics of the data:

In terms of the email addresses, there were 16.5M in total with 4.5M of them not having been seen in previous data breaches already in HIBP. We found 25k of our own individual subscribers in the corpus of data, plus another 20k domain subscribers which is usually organisations monitoring the exposure of their customers (all of these subscribers have now been sent notification emails). As the data was provided to us by law enforcement for the public good, the breach is flagged as subscription free which means any organisation that can prove control of the domain can search it irrespective of the subscription model we launched for large domains in August last year.

The only data we've been provided with is email addresses and disassociated password hashes, that is they don't appear alongside a corresponding address. This is the bare minimum we need to make that data searchable and useful to those impacted. So, let's talk about those standalone passwords:

There are 13.5 million unique passwords of which 8.9M were already in Pwned Passwords. Those passwords have had their prevalence counts updated accordingly (we received counts for each password with many appearing in the takedown multiple times over), so if you're using Pwned Passwords already, you'll see new numbers next to some entries. That also means there are 4.6M passwords we've never seen before which you can freely download using our open source tool. Or even better, if you're querying Pwned Passwords on demand you don't need to do anything as the new entries are automatically added to the result set. All this is made possible by feeding the data into the law enforcement pipeline we built for the FBI and NCA a few years ago.

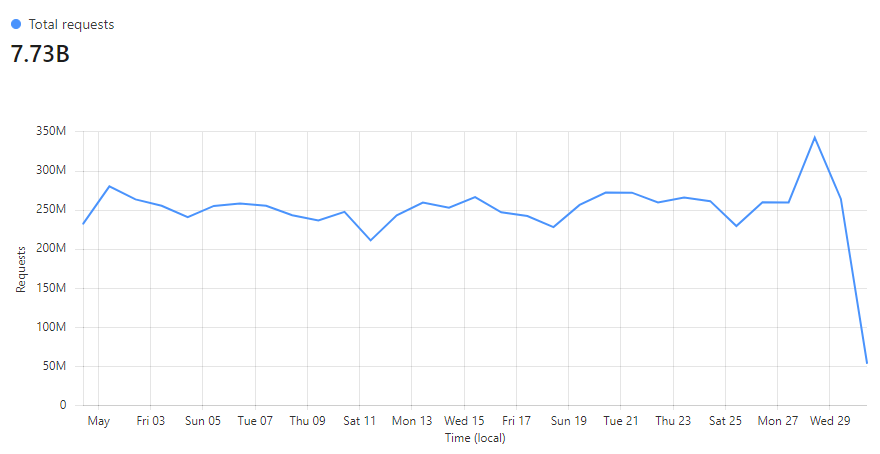

A quick geek-out moment on Pwned Passwords: at present, we're serving almost 8 billion requests per month to this service:

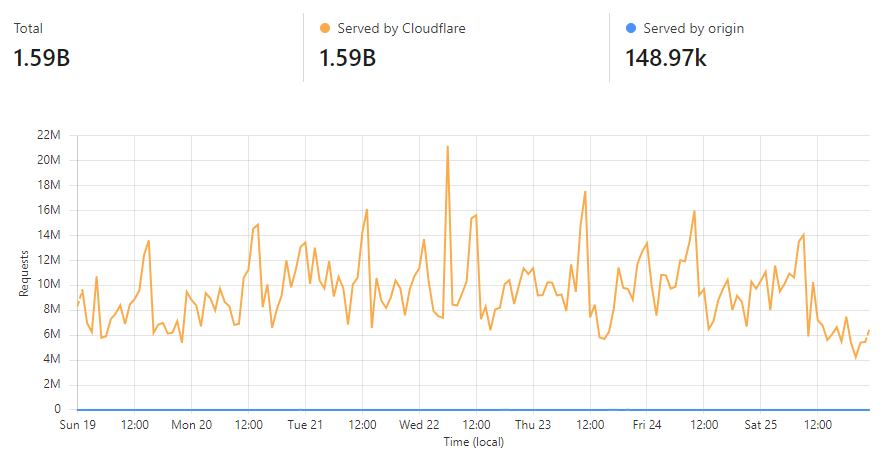

Taking just last week as an example, we're a rounding error off 100% of requests being served directly from Cloudflare's cache:

That's over 99.99% of all requests during that period that were served from one of Cloudflare's edge nodes that sit in 320 cities globally. What that means for consumers of the service is massively fast response times due to the low latency of serving content from a nearby location and huge confidence in availability as there's only about a one-in-ten-thousand chance of the request being served by our origin service. If you'd like to know more about how we achieved this, check out my post from a year ago on using Cloudflare Cache Reserve.

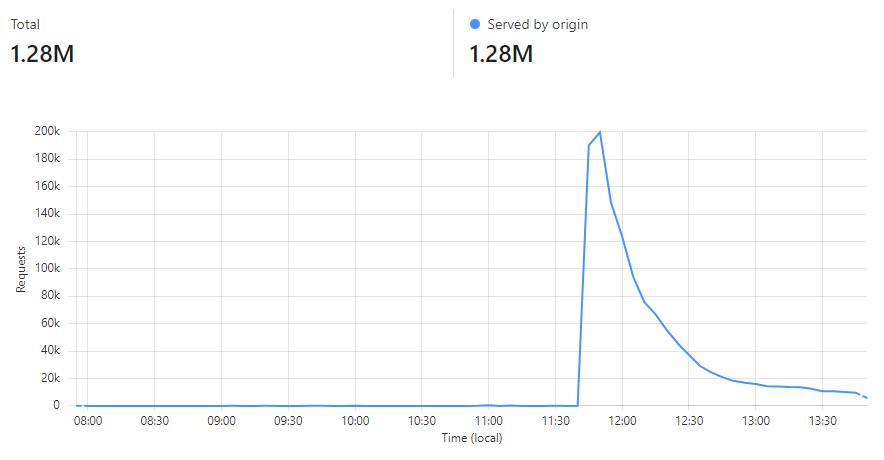

After pushing out the new passwords today, all but 5 hash prefixes were modified (read more about how we use hashes to enable anonymous password searches) so we did a complete Cloudflare cache flush. By the time you read this, almost the entire 16^5 possible hash ranges have been completely repopulated into cache due to the volume of requests the service receives:

Lastly, when we talk about passwords in HIBP, the inputs we receive from law enforcement consist of 3 parts:

- A SHA-1 hash

- An NTLM hash

- A count of how many times the password appears

The rationale for this is explained in the links above but in a nutshell, the SHA-1 format ensures any badly parsed data that may inadvertently include PII is protected and it aligns with the underlying data structure that drives the k-anonymity searches. We have NTLM hashes as well because many orgs use them to check passwords in their own Active Directory instances.

So, what can you do if you find your data in this incident? It's a similar story to the Emotet malware provided by the FBI and NHTCU a few years ago in that the sage old advice applies: get a password manager and make them all strong and unique, turn on 2FA everywhere, keep machines patched, etc. If you find your password in the data (the HIBP password search feature anonymises it before searching, or password managers like 1Password can scan all of your passwords in one go), obviously change it everywhere you've used it.

This operation will be significant in terms of the impact on cybercrime, and I'm glad we've been able to put this little project to good use by supporting our friends in law enforcement who are doing their best to support all of us as online citizens.

https://www.troyhunt.com/operation-endgame/

Published: 2024 05 30 04:25:59

Received: 2024 07 21 13:37:34

Feed: Troy Hunt's Blog

Source: Troy Hunt's Blog

Category: Cyber Security

Topic: Cyber Security

Views: 17