Cyber Security News Aggregator

.Cyber Tzar

provide acyber security risk management

platform; including automated penetration tests and risk assesments culminating in a "cyber risk score" out of 1,000, just like a credit score.Problems in the Parking Lot: Threat Actors Use IRL Quishing to Target Travelers

published on 2024-09-18 08:11:17 UTC by Sam KitsonContent:

This article explores Netcraft’s research into the recent surge in QR code parking scams in the UK and around the globe. Insights include:

- At least two threat groups identified, one of which Netcraft can link to customs tax and postal scams carried out earlier this year.

- Up to 10,000 potential victims identified visiting this group’s phishing websites between June 19 and August 23.

- At least 2,000 form submissions, indicating how much personal data has been extracted from victims, including payment information.

- Evidence suggesting the group is running activity across Europe, including France, Germany, Italy, and Switzerland.

Introduction

Earlier this month, RAC issued an alert for UK motorists to beware of threat actors utilizing Quick Response (QR) code stickers luring them to malicious websites. These sites are designed to exfiltrate personal data, including payment information, by impersonating known parking payment providers. Reports of similar scams across Europe and in Canada and the US have also been increasing and gaining public attention. In the US, the FBI has now issued alert number I-011822-PSA, Cybercriminals Tampering with QR Codes to Steal Victim Funds, to raise awareness. We can expect that these attacks will continue to be deployed on a global scale.

In the UK, phishing activity is peaking. On July 30, Southampton City Council posted on Facebook warning motorists of a wave of malicious QR codes appearing across the city center. Printed on adhesive stickers and affixed to parking meters, the QR codes directed users to phishing websites impersonating the parking payment app brand PayByPhone. Around the same time, several Netcraft staff shared stories of family members being duped by similar scams. In response, Netcraft deployed its research teams to analyze and understand the activity in depth.

Fig. 1. Southampton City Council’s post on Facebook warning users to avoid scanning the QR codes and explaining the risk.

Looking at British media reports, these parking QR code scams appeared to peak during the summer holiday period (June to September). Activity concentrated in and around coastal tourism locations such as Blackpool, Brighton, Portsmouth, Southampton, Conwy, and Aberdeen. There are now at least 30 parking apps in the UK, varying by location—an abundance that benefits criminals. By targeting tourist destinations, threat actors can prey on tourists who need to download the parking payment apps and are searching for ways to do so.

Netcraft was able to identify two threat groups running such scams. This report focuses on an active group impersonating the PayByPhone brand. The other group has been identified using a phishing kit to simulate multiple brands, including RingGo.

How do Parking QR Code Scams work?

Mobile payments are now standard in many public and private parking lots across the world. While transactions were once used to involve calling or texting a number, mobile apps have become more commonplace.

In the UK, the main providers include PayByPhone, RingGo, JustPark, ParkMobile, and MiPermit. Providers display user instructions in parking lots, typically on parking meters. These include a download link or QR code to access the payment app, as well as a unique location code to geolocate the user. This approach not only offers an opportunity for threat actors to target victims on-site, it may also enable them to further target victims with additional location-specific malicious messages.

Step-by-step process

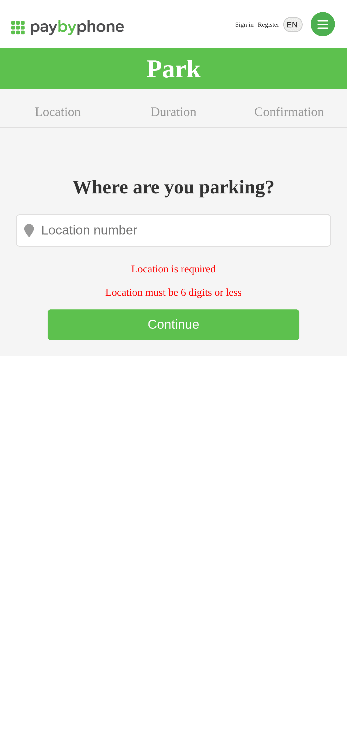

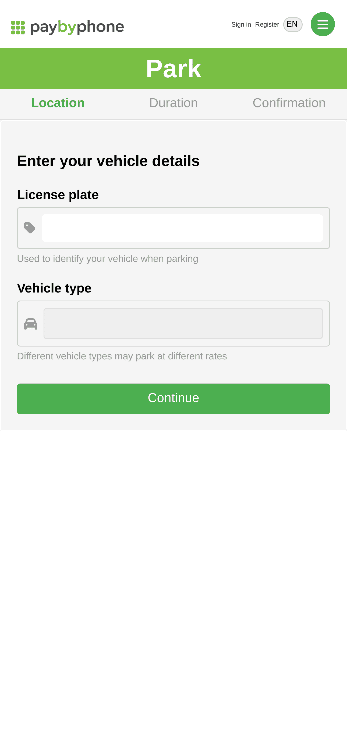

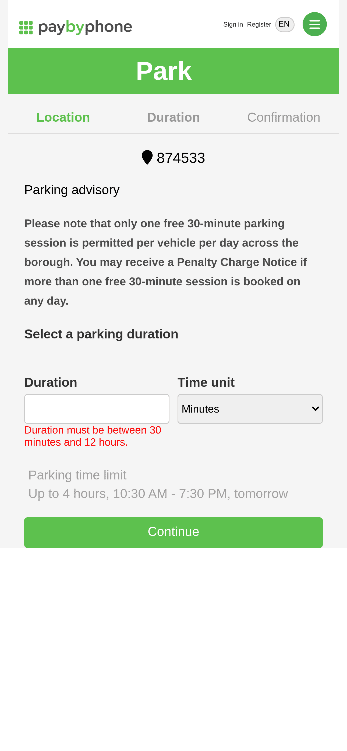

Based on the PayByPhone threat group which forms the basis of the research, the following step-by-step process being used to extract victim data was observed:

- Threat actor acquires and deploys “boots on the ground” resources to set up the attack.

- Malicious QR codes are affixed to parking lot payment machines.

- A victim visiting that parking lot scans the malicious QR code and is directed to a mobile phishing website mimicking a legitimate parking lot payment provider.

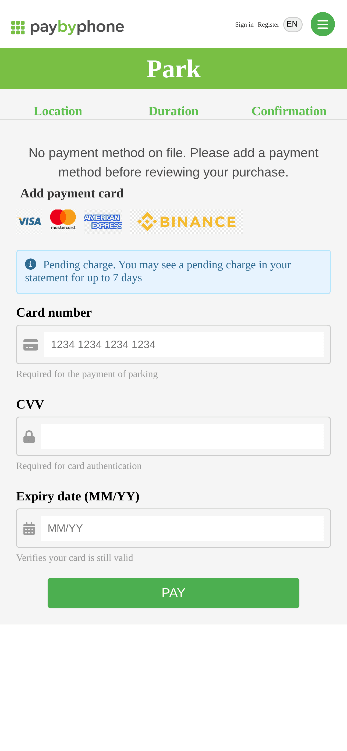

- The phishing website prompts the victim to enter the following details in this order:

- Their 6-digit parking lot location code.

- Vehicle details, including license plate and vehicle type

- Parking duration

- Payment card details

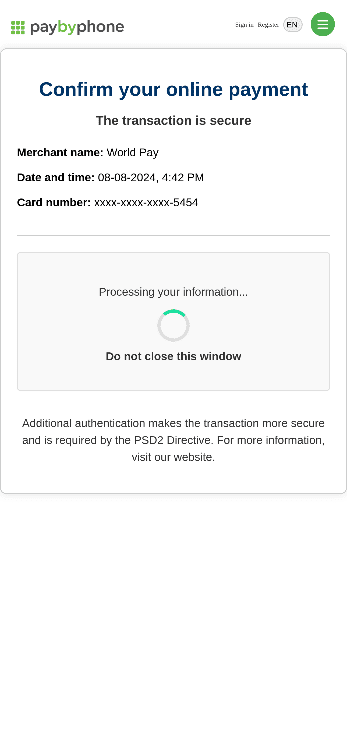

- The website then displays a fake “Processing” page, simulating a familiar user experience. In some cases, a 3D secure code will be prompted from the victim’s bank/card provider.

- The victim is redirected to a “Payment accepted!” page.

- The phishing website confirms the victim’s entered details.

- The victim is directed to the official PayByPhone website.

Fig. 2. Screenshots showing the step-by-step process on one of the fake PayByPhone websites.

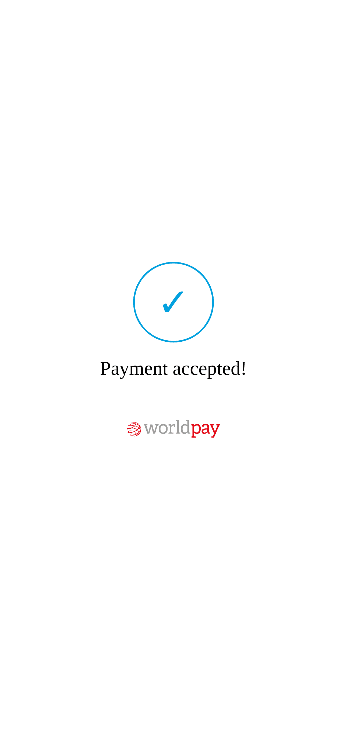

Following payment, phishing kit groups send the victim to a failed payment page, prompting them to use an alternative payment card. This extends the volume of credentials and funds the threat actor can exfiltrate.

Fig. 3. Screenshot of fake failed payment page on one of the malicious websites.

Tactics

Netcraft has been able to analyze threat actor activity to understand the strategies underpinning these attacks.

Timeline of activity

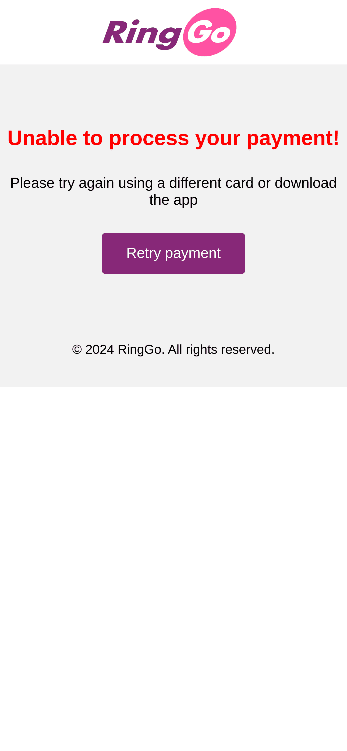

Fig. 4. Chart showing malicious websites being activated and deactivated between June 17 and September 3.

In the timeline above:

- June 19: the scam begins; the first phishing websites appear, but these are taken offline after approximately one week.

- June 28: the scam reappears online behind a new domain name.

- July 2: threat actor registers two new domains, which redirect victims back to the initial websites.

- July 27: websites continuously come online, as others gradually go offline.

- Early August: more domains are registered every few days, but some only stay online for a short time and before any QR codes are used1.

- Mid-August: all known phishing websites go down; threat actor registers new domains showing variations to the format (using phrases like parkbyphone instead of pbp, and others that only refer to QR codes and scanning).

- They register them in pairs with a .info domain hosting the actual phishing website and a .click equivalent redirecting to the .info version. Likely due to news coverage, these only remain online for a few days at a time and are quickly taken offline by the domain registrar.

- Late August onwards: the same pattern of registering new domains multiple times per week continues. The threat actor experiments with different top-level domains (TLDs) (.live and .online) to evade detection. Each site remains online for a few days, in contrast to the start of the campaign when sites were live for up to a month.

Website characteristics

Numerous phishing websites were created to facilitate these attacks. Since June 17, Netcraft has seen the same scam on 32 distinct domain names. All of these demonstrated the following characteristics:

- Registered with NameSilo

- Using .info, .click, .live, .online, and .site TLDs

- Protected with Cloudflare

The QR codes most typically linked directly to .click URLs, which redirected to a live phishing website at a .info or .site URL. This could be a persistence tactic to ensure that if the group’s core sites are taken down, new ones can be set up, and the redirects changed. Such an approach avoids the need to physically replace any QR code stickers, keeping the attack online while controlling costs.

On-the-ground tactics

After tracking the threat actor’s activity online throughout August, the Netcraft team then went a step further to gather additional on-the-ground research.

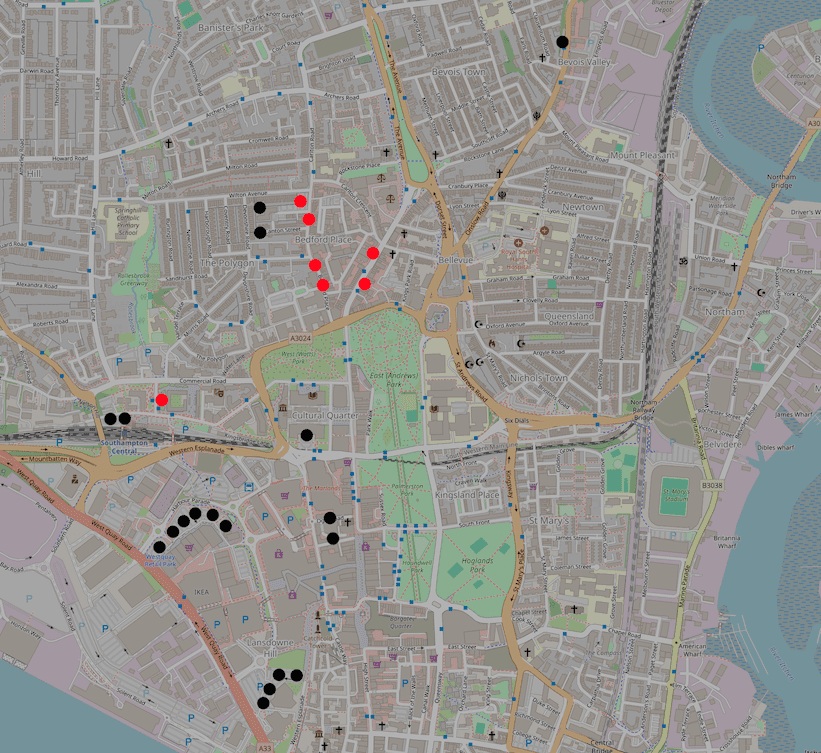

Fig. 5. Map showing Netcraft-identified parking meters displaying the location of benign (black) and malicious (red) QR codes across Southampton city center.

Of the 24 parking meters across Southampton City Center, seven are used to display malicious QR codes. Some of these were in prime locations, including opposite Southampton Central train station and near a large grocery store. Other areas in the city center and Portswood (another high foot traffic area) appeared to be clear of QR codes.

The QR code stickers appear to have been distributed in a single batch—all linking to the same website—following the takedown of several of the threat actor’s websites. This highlights the persistent continuation of the campaign, with the threat actor rotating websites and remaining active despite their operations being disrupted.

The domain name for the website mentioned above was registered on the afternoon of Sunday, August 25. The first visit was at approximately 07:00 the next morning. Netcraft researchers believe that this was the threat actor’s on-the-ground agent testing the QR code after placing the stickers. These timelines highlight the speed of activity between registering a new domain and placing a corresponding QR code sticker.

In Southampton city center, there are two types of parking meters—red, which represent more dated models, and black, which are newer and display official PayByPhone branding. The threat actor’s QR codes were only found on these new black meters, pasted on top of the official branding to improve impersonation.

Some meters had been pasted with three QR code stickers (front and both sides), but not all. At the time of visit, one meter on London Road had its front QR code sticker partially ripped off. Together, these observations may suggest either that stickers are being haphazardly removed, missed, or that the individuals responsible for planting them are inconsistent in their approach.

Fig. 6. Photo of parking meter with QR code partially removed

The main takeaway from the on-the-ground research is that the threat actor has invested strategy and resources to achieve greater impact—making use of high-footfall areas and using tactics that add legitimacy to the scam. It’s clear that the measures being taken on the ground to deter these attacks are not as effective as takedowns online.

Detection evasion tactics

We were able to identify the following detection evasion tactics:

- Bot detection and Traffic Distribution Systems (TDS) being used to evade detection.

- Websites redirecting to badrobot[.]com based on the browser’s reported User Agent HTTP header.

- Threat actors appear to have an approved list of User Agents including most recent versions of popular iOS and Android browsers. If the QR codes are scanned from any other device or browser, redirection occurs.

- Cloudflare protection enabled on some websites using Captcha to gate user access.

- Websites that detect suspected bot activity redirecting the user to an error page prompting them to rescan the QR code.

Impact of these attacks

Some of the most critical intelligence we’ve been able to gather on these attacks concerns their impact on victims.

What data has been exfiltrated and how?

As illustrated in the step-by-step flow earlier in this earlier, the threat actor used webforms on their phishing website to capture and store victim data including:

- License plate

- Vehicle type

- Location code

- Complete payment card details, including security code

This personally identifiable information (PII) could be used in future phishing attacks, for example, utilizing the threat actor’s knowledge of the victim’s vehicle, including location-based campaigns that utilize the victim’s location codes.

After each form is submitted, the phishing websites submit victims’ data to the server. This maximizes the amount of information gathered, i.e., even if the victim exits the site before completing the entire process.

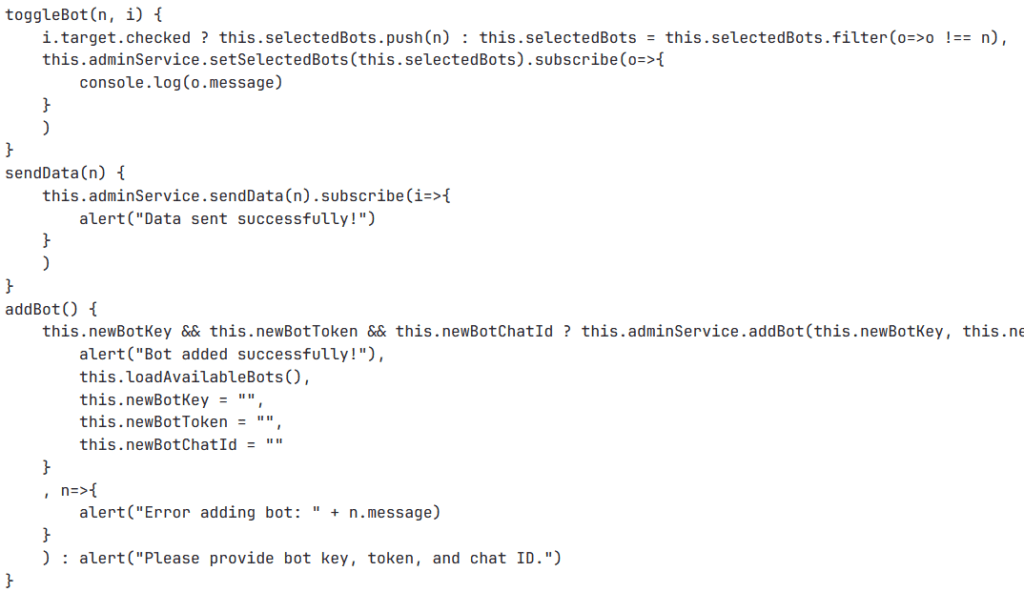

The research suggests that the stolen data is then stored temporarily on the web server before being sent on to the threat actor via a Telegram bot2. An admin control panel on the website is used to configure the API keys for these bots and select which to send data to (default bot names are: “main” and “Hulingans”.)

Fig. 7. Screenshot showing the app admin panel used to configure bot API keys.

How many victims are there?

Netcraft’s research identified an approximate number of victims affected by these attacks.

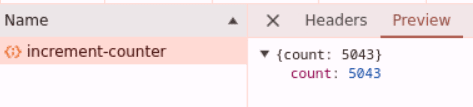

On one of the threat actor’s websites, an API call to increment a visitor counter. The response displays the number of website visitors to date. By tracking the visitor counter over a few days, it was revealed that:

- ~13 visitors per hour

- ~320 visitors visit per day (with an increase at weekends)

From June 19 to August 23, 10,000 users accessed this website and another mirror site. Many of these users could be potential victims who have scanned one of the malicious QR codes.

Fig. 8. Screenshot showing the website increment counter and number of website visitors.

How much data was stolen?

Two of the threat actor’s phishing websites featured an exposed debugging API endpoint showing the number of form submissions (i.e., every time a user submitted data through the malicious website forms). On one of these sites, Netcraft was able to identify 1,932 form submissions from mid-June to August 12. On the other, 267 details were collected from July 27 and August 20. This brings the logged total to 2,199. Although the other websites had this endpoint disabled. It can be assumed that across all of the malicious sites, more data was exfiltrated, including victims’ payment details3.

Threat actor profile

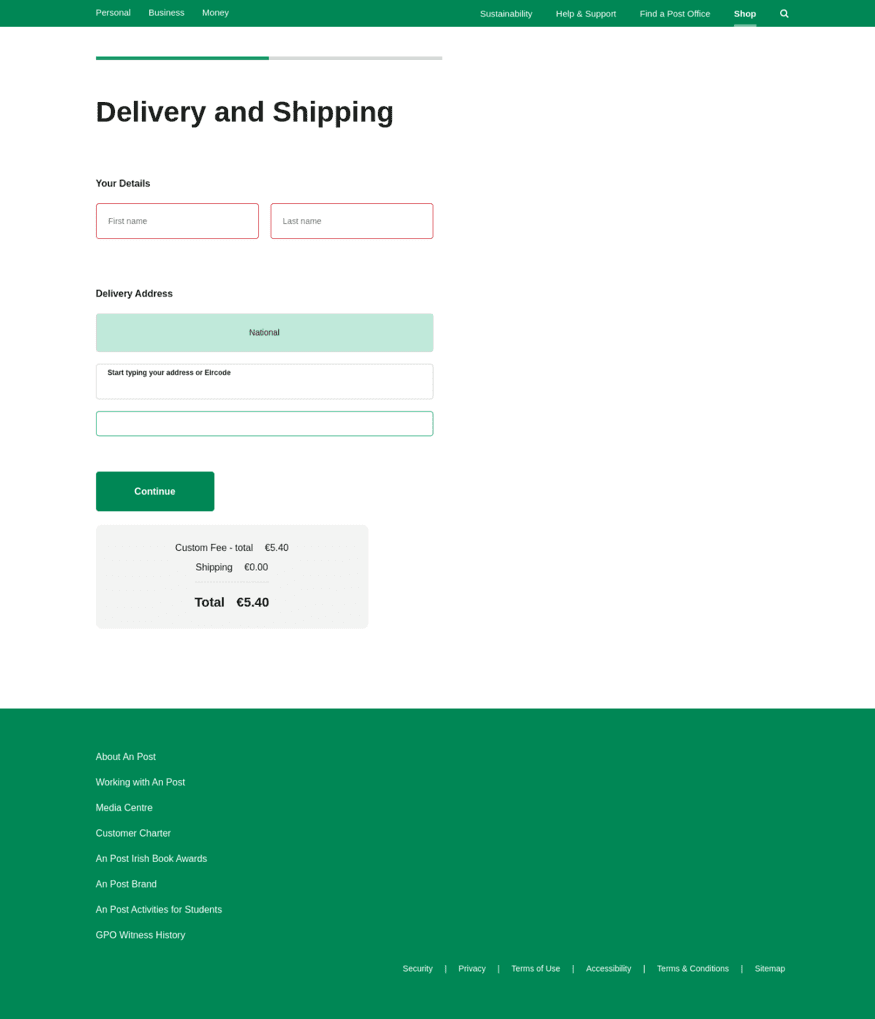

Netcraft has found indications that the threat actor studied in the research is related to a series of postal and customs tax-themed scams targeting Ireland and Poland. These indicators include:

- Corresponding redirect behavior (for detection evasion)

- Web servers running the same software version

- Use of the same domain registrar

- Use of Cloudflare with a very similar configuration

The step-by-step flow for extracting victim data is also similar. The customs tax scam was observed requesting the following data under the guise of releasing a parcel held at customs or a postal depot:

- The victim’s phone number

- Their address and other shipping information

- Payment details to release the parcel and have it shipped to the victim

The following timeline helps demonstrate how the threat actor switched between their campaigns:

- Three customs tax/postal scam websites first seen in February and March 2024 staying online for around two months.

- Between May 12 and June 14, nine more domains registered (most inactive), some of which featured customs tax scams for approximately one week maximum.

- After this point, the customs tax websites lay dormant while the first parking scam websites came online.

- From July 19, four new domains were registered hosting the same website as before; two went down within a week, but the others remained online for over a month.

- These websites have been manually disabled by the attacker, although this is likely to be a temporary measure.

We believe this shows that when the threat group’s parking scam became disrupted by takedown activity, they reactivated their previous campaign.

Fig. 9. Screenshot showing a page from the customs tax website.

Threat actor geography

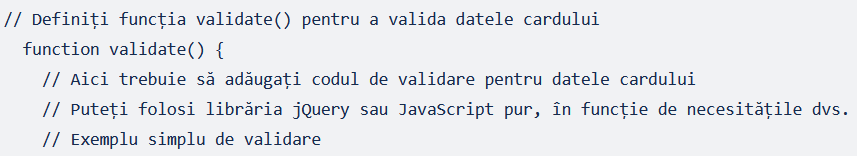

Netcraft was not able to find conclusive evidence pinning down the threat actor’s geographical location. However, a comment was found in the source code of one website containing a Romanian expletive: console.log(‘sloboz’).

Another section of the source code contains comments in Romanian (translation: “Define the validate function to validate the card data validate function / Here you must add the validation code for the card data / You can use the jQuery library or pure Javascript, depending on your needs / Simple validation example”).

Fig. 10. Screenshot showing Romanian language text in website source code.

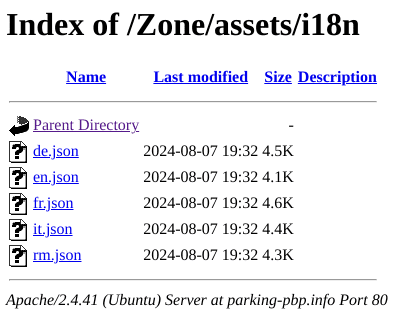

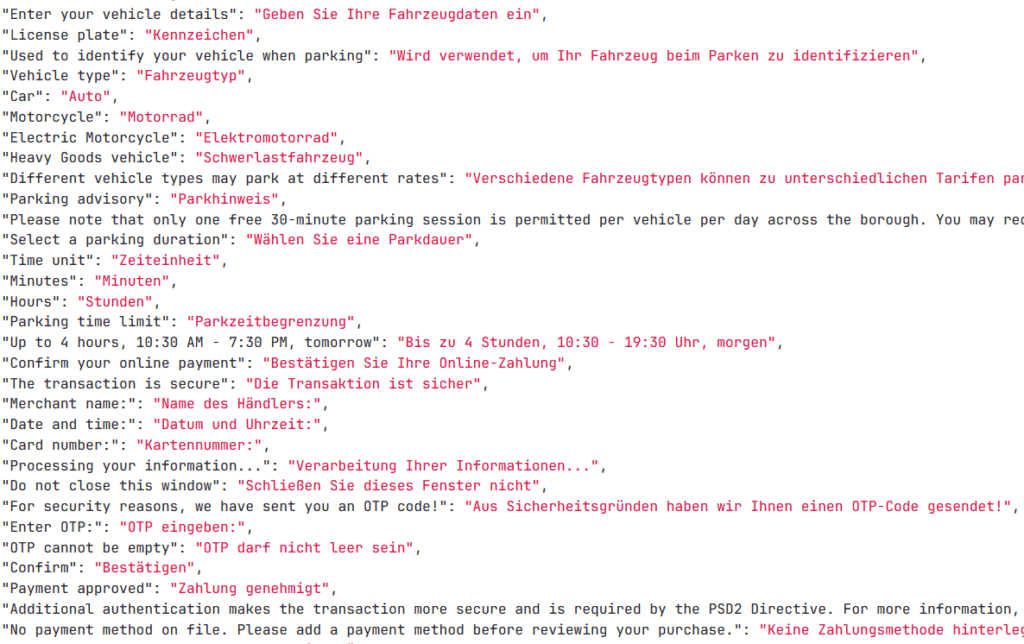

The phishing websites contain internationalization files for English, French, German, Italian, and Romansh (spoken in Switzerland), indicating that this attack is being deployed on a trans-European scale. This backs up news reports from both Switzerland and France where have been found linking to the same phishing websites

Fig. 11 and 12. Screenshots showing translation files stored in the website.

Conclusion

Netcraft’s research into these parking lot QR code attacks highlights the tip of a much bigger iceberg. The insights drawn provide valuable insight into the criminals carrying them out, informing how organizations can best defend themselves.

The behaviors and characteristics of the threat actor identified through the analysis demonstrates the scale and strategic approach being used. Not only is this one criminal group operating across a continent, but they are also investing to evade detection and achieve continuous operation. Additionally the criminal group is likely responsible for a number of other attacks. This shows how cybercrime groups adapt and evolve their tactics and respond to opportunities that yield greater impact.

If you want to know more about how we detect, analyze, and take down attacks like these, get in touch with the team or book a demo now.

Footnotes

1 We may assume that the prevalence of this topic in the news in August influenced takedown activity.

2 Data exfiltration via Telegram is a common asset stored in phishing kits. Email used to be the most favoured channel, but as email takedown has advanced, threat actors have adapted. Telegram offers threat actors the ability to easily switch between Telegram bots to receive exfiltrated data. It also enables them to relay data to multiple Telegram bots, enabling them to maintain persistence if one bot is disabled.

3 In adhering to the Computer Misuse Act, we’re unable to confirm the exact number of exfiltrated payment details, as this would require directly accessing stolen data via the admin control panel.

https://www.netcraft.com/blog/irl-quishing-scams-target-travelers/

Published: 2024 09 18 08:11:17

Received: 2024 09 18 15:19:31

Feed: Netcraft

Source: Netcraft

Category: Cyber Security

Topic: Cyber Security

Views: 20